Chinook – Deadman’s Island

It is dusk on the Lost Lagoon,

And we two dreaming the dusk away,

Beneath the drift of a twilight gray-Beneath the drowse of an ending day

And the curve of a golden moon.

It is dark in the Lost Lagoon,

And gone are the depths of haunting blue,

The grouping gulls, and the old canoe,

The singing firs, and the dusk and — you,

And gone is the golden moon.

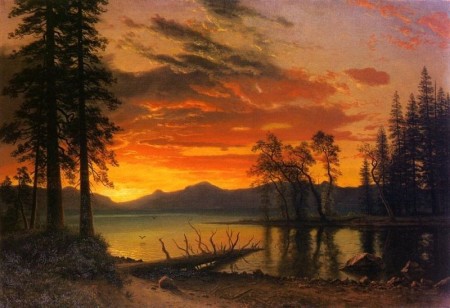

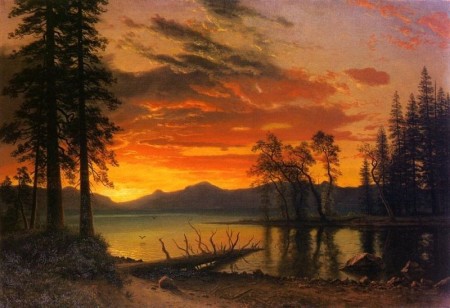

Art by Albert Bierstadt.

O! lure of the Lost Lagoon-I dream tonight that my paddle blurs The purple shade where the seaweed stirs-I hear the call of the singing firs In the hush of the golden moon.

FOR many minutes we stood silently, leaning on the western rail of the bridge as we watched the sun set across that beautiful little basin of water known as Coal Harbor. I have always resented that jarring, unattractive name, for years ago, when I first plied paddle across the gunwale of a light little canoe that idled above its margin, I named the sheltered little cove the Lost Lagoon. This was just to please my own fancy, for as that perfect summer month drifted on, the ever-restless tides left the harbor devoid of water at my favorite canoeing hour, and my pet idling place was lost for many days-hence my fancy to call it the Lost Lagoon. But the chief, Indian-like, immediately adopted the name, at least when he spoke of the place to me, and as we watched the sun slip behind the rim of firs, he expressed the wish that his dugout were here instead of lying beached at the farther side of the park.

“If canoe was here, you and I we paddle close to shores all ’round your Lost Lagoon: we make track just like half moon. Then we paddle under this bridge, and go channel between Deadman’s Island and park. Then ’round where cannon speak time at nine o’clock. Then ‘cross Inlet to Indian side of Narrows.”

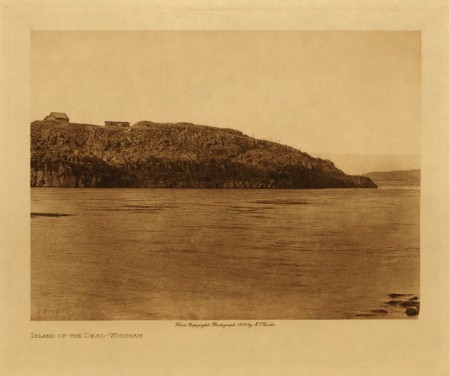

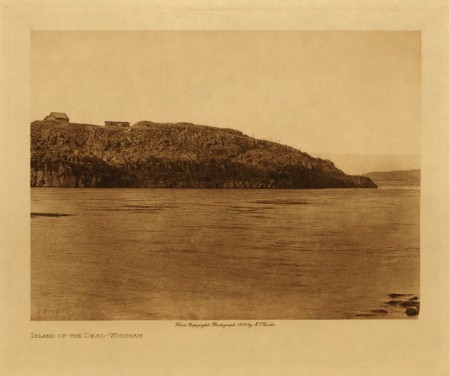

Unknown photo from 1909.

I turned to look eastward, following in fancy the course he had sketched; the waters were still as the footstep of the oncoming twilight, and, floating in a pool of soft purple, Deadman’s Island rested like a large circle of candle moss. “Have you ever been on it?” he asked as he caught my gaze centering on the irregular outline of the island pines.

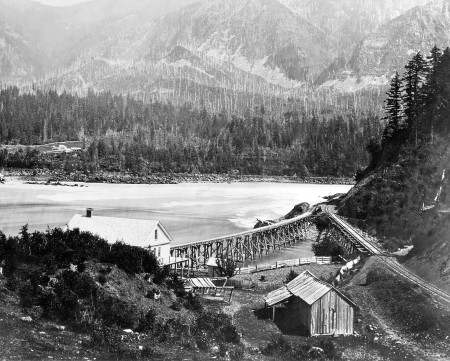

Island of the Dead (Wishram) Edward S. Curtis photo.

“I have prowled the length and depth of it,” I told him. “Climbed over every rock on its shores, crept under every tangled growth of its interior, explored its overgrown trails, and more than once nearly got lost in its very heart.” “Yes,” he half laughed, “it pretty wild; not much good for anything.” “People seem to think it valuable,” I said. “There is a lot of litigation — of fighting going on now about it.”

“Oh! that the way always,” he said as though speaking of a long accepted fact. “Always fight over that place. Hundreds of years ago they fight about it; Indian people; they say hundreds of years to come everybody will still fight — never be settled what that place is, who it belong to, who has right to it. No, never settle. Deadman’s Island always mean fight for someone.”

“So the Indians fought amongst themselves about it?” I remarked, seemingly without guile, although my ears tingled for the legend I knew was coming. “Fought like lynx at close quarters,” he answered. “Fought, killed each other, until the island ran with blood redder than that sunset, and the sea water about it was stained flame color — it was then, my people say, that the scarlet fire-flower was first seen growing along this coast.”

“It is a beautiful color — the fire-flower,” I said.

“It should be fine color, for it was born and grew from the hearts of fine tribes-people-very fine people,” he emphasized.

We crossed to the eastern rail of the bridge, and stood watching the deep shadows that gathered slowly and silently about the island; I have seldom looked upon anything more peaceful.

The chief sighed. “We have no such men now, no fighters like those men, no hearts, no courage like theirs. But I tell you the story; you understand it then. Now all peace; tonight all good Tillicum’s; even dead man’s spirit does not fight now, but long time after it happen those spirits fought.”

“And the legend?” I ventured.

“Oh! yes,” he replied, as if suddenly returning to the present from out a far country in the realm of time. “Indian people, they call it the ‘Legend of the Island of Dead Men.’

“There was war everywhere. Fierce tribes from the northern coast, savage tribes from the south all met here and battled and raided, burned and captured, tortured and killed their enemies. The forests smoked with camp fires, the Narrows were choked with war canoes, and the Sagalie Tyee — He who is a man of peace — turned His face away from His Indian children. About this island there was dispute and contention. The medicine men from the North claimed it as their chanting ground. The medicine men from the South laid equal claim to it. Each wanted it as the stronghold of their witchcraft, their magic. Great bands of these medicine men met on the small space, using every sorcery in their power to drive their opponents away. The witch doctors of the North made their camp on the northern rim of the island; those from the South settled along the southern edge, looking towards what is now the great city of Vancouver. Both factions danced, chanted, burned their magic powders, built their magic fires, beat their magic rattles, but neither would give way, yet neither conquered. About them, on the waters, on the mainland’s, raged the warfare of their respective tribes — the Sagalie Tyee had forgotten His Indian children.

“After many months, the warriors on both sides weakened. They said the incantations of the rival medicine men were bewitching them, were making their hearts like children’s, and their arms nerveless as women’s. So friend and foe arose as one man and drove the medicine men from the island, hounded them down the Inlet, herded them through the Narrows and banished them out to sea, where they took refuge on one of the outer islands of the gulf. Then the tribes once more fell upon each other in battle.

“The warrior blood of the North will always conquer. They are the stronger, bolder, more alert, more keen. The snows and the ice of their country make swifter pulse than the sleepy suns of the South can awake in a man; their muscles are of sterner stuff, their endurance greater. Yes, the northern tribes will always be victors.* But the craft and the strategy of the southern tribes are hard things to battle against. While those of the North followed the medicine men farther out to sea to make sure of their banishment, those from the South returned under cover of night and seized the women and children and the old, enfeebled men in their enemy’s camp, transported them all to the Island of Dead Men, and there held them as captives. Their war canoes circled the island like a fortification, through which drifted the sobs of the imprisoned women, the mutterings of the aged men, the wail of little children.

“Again and again the men of the North assailed that circle of canoes, and again and again were repulsed. The air was thick with poisoned arrows, the water stained with blood. But day by day the circle of southern canoes grew thinner and thinner; the northern arrows were telling and truer of aim. Canoes drifted everywhere, empty, or worse still, manned only by dead men. The pick of the southern warriors had already fallen, when their greatest Tyee mounted a large rock on the eastern shore. Brave and unmindful of a thousand weapons aimed at his heart, he uplifted his hand, palm outward — the signal for conference.

Instantly every northern arrow was lowered, and every northern ear listened for his words.

“‘Oh! men of the upper coast,’ he said, ‘you are more numerous than we are; your tribe is larger; your endurance greater. We are growing hungry, we are growing less in numbers. Our captives — your women and children and old men — have lessened, too, our stores of food. If you refuse our terms we will yet fight to the finish. Tomorrow we will kill all our captives before your eyes, for we can feed them no longer, or you can have your wives, your mothers, your fathers, your children, by giving us for each and every one of them one of your best and bravest young warriors, who will consent to suffer death in their stead. Speak! You have your choice.’

“In the northern canoes scores and scores of young warriors leapt to their feet. The air was filled with glad cries, with exultant shouts. The whole world seemed to ring with the voices of those young men who called loudly, with glorious courage:

“‘Take me, but give me back my old father.’

“‘Take me, but spare to my tribe my little sister.’

“‘Take me, but release my wife and boy baby.’

“So the compact was made. Two hundred heroic, magnificent young men paddled up to the island, broke through the fortifying circle of canoes and stepped ashore. They flaunted their eagle plumes with the spirit and boldness of young gods. Their shoulders were erect, their step was firm, their hearts strong. Into their canoes they crowded the two hundred captives. Once more their women sobbed, their old men muttered, their children wailed, but those young copper-colored gods never flinched, never faltered. Their weak and their feeble were saved. What mattered to them such a little thing as death?

“The released captives were quickly surrounded by their own people, but the flower of their splendid nation was in the hands of their enemies, those valorous young men who thought so little of life that they willingly, gladly laid it down to serve and to save those they loved and cared for. Amongst them were war-tried warriors who had fought fifty battles, and boys not yet full grown, who were drawing a bow string for the first time, but their hearts, their courage, their self-sacrifice were as one.

“Out before a long file of southern warriors they stood. Their chins uplifted, their eyes defiant, their breasts bared. Each leaned forward and laid his weapons at his feet, then stood erect, with empty hands, and laughed forth their challenge to death. A thousand arrows ripped the air, two hundred gallant northern throats flung forth a death cry exultant, triumphant as conquering kings — then two hundred fearless northern hearts ceased to beat.

“But in the morning the southern tribes found the spot where they fell peopled with flaming fire-flowers. Dread terror seized upon them. They abandoned the island, and when night again shrouded them they manned their canoes and noiselessly slipped through the Narrows, turned their bows southward and this coast line knew them no more.”

“What glorious men,” I half whispered as the chief concluded the strange legend.

“Yes, men!” he echoed. “The white people call it Deadman’s Island. That is their way; but we of the Squamish call it The Island of Dead Men.”

The clustering pines and the outlines of the island’s margin were now dusky and indistinct. Peace, peace lay over the waters, and the purple of the summer twilight had turned to gray, but I knew that in the depths of the undergrowth on Deadman’s Island there blossomed a flower of flaming beauty; its colors were veiled in the coming nightfall, but somewhere down in the sanctuary of its petals pulsed the heart’s blood of many and valiant men.

Chinook Texts by Franz Boas. [1894] (U.S. Bureau of American Ethnology Bulletin, no 20.)