Written by: James D. Keyser, Indian rock art of the Columbia Plateau

Rock art is one of the most common types of archaeological site in Oregon, occurring from the Portland Basin to Hell’s Canyon and the high desert canyons along the Owyhee River to far southwestern Oregon’s Rogue River drainage. Including both pictographs (paintings) and petroglyphs (carvings), the rock art at these sites was created as early as 7,000 years ago until as recently as the late 1800s. Although petroforms—a third type of rock art composed of outlines cut in desert pavement or boulders laid out in the form of animals or humans—are found elsewhere in North America, none has been discovered in Oregon.

Including both pictographs (paintings) and petroglyphs (carvings), the rock art at these sites was created as early as 7,000 years ago until as recently as the late 1800s. Although petroforms—a third type of rock art composed of outlines cut in desert pavement or boulders laid out in the form of animals or humans—are found elsewhere in North America, none has been discovered in Oregon.

Archaeologists have classified Oregon’s rock art into five traditions, that is, spatially broad-based artistic expressions that were created during a defined period of time. The traditions generally follow Oregon’s aboriginal ethnic/cultural boundaries. Thus, the Columbia Plateau Tradition reflects the art of Sahaptian-speaking tribes such as the Tenino, Nez Perce, Umatilla, and Klamath-Modoc, while the Great Basin Tradition comprises the art of the Numic-speaking bands of the Northern Paiute. In the river valleys of western Oregon, the few sites that are known represent the Columbia Plateau Tradition and a little-known California rock art expression called the Far Western Pit and Groove Tradition, which is the product of Tututni and Kalapuya artists and probably members of other tribes as well.

Cover to book text is from.

Biographic rock art is the sole Oregon rock-art tradition that was made by several distinctly different ethnic groups. Occurring primarily in the canyon country of northeastern Oregon, the art was created by Cayuse, Nez Perce, Umatilla, and Paiute artists to portray the acquisition of horses and guns and the war honors of important men. This art is known only from the 250-year period between about A.D. 1650 and 1900.

The subject matter of rock art in the Columbia Plateau Tradition is primarily humans, animals, and geometric designs, one of the most common of which is tally marks—a horizontally oriented series of three to more than thirty short, vertical, evenly spaced, finger-painted lines. Despite its limited subject matter, Columbia Plateau art functioned in several ways, including as a commemoration of the acquisition of spirit power during a vision quest and as a shaman’s ritual expression of power.

Yakima Polychrome designs and the closely related imagery of the Columbia River Conventionalized Style of the Northwest Coast Tradition served in healing and mortuary rituals and were used to witness mythic beings and places. Some images of animals and hunters in the Columbia Plateau Tradition were painted and carved as hunting magic. In the Klamath Basin, art in the Columbia Plateau Tradition has several stylistic expressions, but current research suggests that all of them were the exclusive purview of shamans.

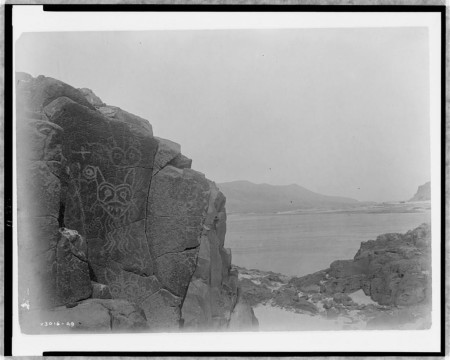

Columbia River Gorge

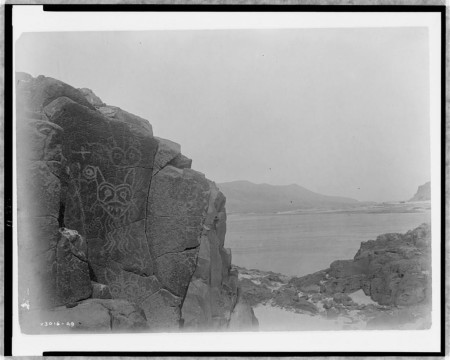

Rock art in the Northwest Coast Tradition is limited in Oregon to a site at Willamette Falls, a few sites in The Dalles-Deschutes region, along the lower Deschutes and John Day Rivers, and in one rock shelter near the head of the North Umpqua River. Images are mainly of fantastic spirit beings, represented either by elaborate faces with grinning, teeth-filled mouths, concentric circle eyes, and exaggerated ears and headdresses or by owls, lizards, snakes, and water monsters. These spirit beings include some named beings such as Swallowing Monster, She Who Watches, Cannibal Woman, and Spedis Owl, but the names and identities of many others are lost in time. Ethnographic sources indicate that these images were made by shamans in their curing and mortuary rituals and to witness mythological happenings.

Far Western Pit and Groove Tradition rock art is found from the southern Willamette Valley near Eugene into the Umpqua and Rogue River drainages, where it occurs as cupules—shallow dimples—and simple geometric forms pecked and ground into streamside boulders. Known as Baby Rocks or Rain Rocks, ethnographic sources indicate that these simple petroglyphs were carved both by shamans accessing and using supernatural power to call the salmon and communicate with the gods and by women who wanted to bear a child.

Vantage, WA.

Great Basin Tradition rock art has both the broadest statewide distribution and the greatest number of Oregon sites. Found across the southeastern third of the state and along the Snake River from Ontario, Oregon, to Clarkston, Washington, Great Basin imagery is dominated by abstract symbols such as circle chains, grids, zigzag lines, nucleated and concentric circles, curvilinear mazes, and dot patterns. Many sites also have cupules pecked into rock surfaces. Stick-figure humans and lizards, deer, and mountain sheep are the primary representational images, but these almost always occur as only a few figures at any one site, even those with hundreds to thousands of geometric designs.

Certainly much Great Basin rock art was made by shamans who were acquiring or using supernatural power, and much of the geometric imagery may have been generated in the artists’ minds by stimuli experienced during a trance. Other Great Basin imagery, however, is likely to have been made in conjunction with subsistence activities during the seasonal round of these high-desert hunter-gatherers and likely had a broader function as part of the rituals associated with subsistence.

Including both pictographs (paintings) and petroglyphs (carvings), the rock art at these sites was created as early as 7,000 years ago until as recently as the late 1800s. Although petroforms—a third type of rock art composed of outlines cut in desert pavement or boulders laid out in the form of animals or humans—are found elsewhere in North America, none has been discovered in Oregon.

Including both pictographs (paintings) and petroglyphs (carvings), the rock art at these sites was created as early as 7,000 years ago until as recently as the late 1800s. Although petroforms—a third type of rock art composed of outlines cut in desert pavement or boulders laid out in the form of animals or humans—are found elsewhere in North America, none has been discovered in Oregon.

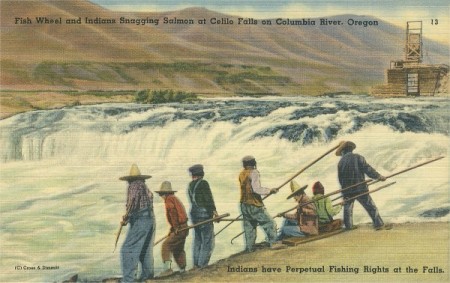

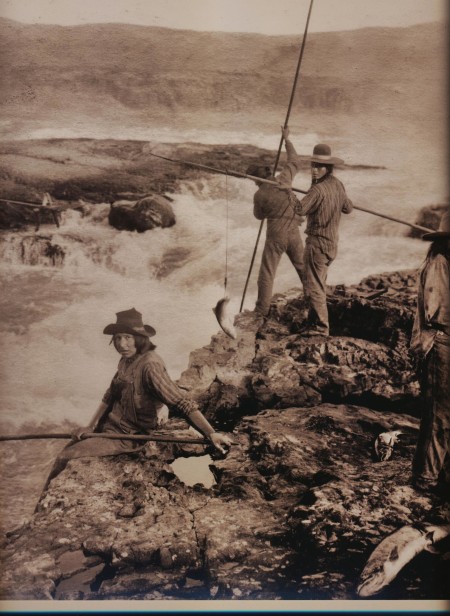

was part of a substantial population that refused to settle or stay on the reservations. Many of them came to identify themselves as Columbia River Indians, or River People, based on their shared heritage of connection to the river, resistance to the reservation system, adherence to cultural traditions, and relative detachment from the institutions of federal control and tribal governance. ”

was part of a substantial population that refused to settle or stay on the reservations. Many of them came to identify themselves as Columbia River Indians, or River People, based on their shared heritage of connection to the river, resistance to the reservation system, adherence to cultural traditions, and relative detachment from the institutions of federal control and tribal governance. ”