he spoke to me in a language lost. – Backworld

The road from Taos to Farmington cuts through bone-dry land and time. It begins in the shadow of Taos Mountain,

where the air feels like it holds everything—war, survival, songs older than any book. The pueblo stands behind me, its adobe walls cracked but breathing, holding the stories of a thousand fires.

I leave as the sun rises low, painting the world in gold and blood. The sky stretches wide, too big to hold onto, and the Sangre de Cristo peaks glow like embers, watching as I drive, chasing my shadow. My hands grip the wheel, my heart pounding with a rhythm that matches the hum of the rough terrain tires. (a must for any desert rat)

I am heading north to see her. To cross through time and space and all the weight that lies in between.

The road curves, and the landscape shifts. Past Abiquiú, the earth opens wide, mesas rising like the backs of sleeping giants. These stones have been here longer than memory, their edges worn by the wind and the prayers of the ancianos. The ghosts of the Tewa, the Diné, the ancestors, and the spirits of this land still walk here, their voices carried in the soft susurro of the sagebrush.

The ruins of Chaco Canyon call from the west, their silence louder than any hymn. Here, the Ancestral Puebloans raised walls to touch the stars, their kivas spiraling downward like roots into the earth. They built with precision, with reverence, aligning their lives to the solstice, the equinox, the turning of the heavens.

But the ruins are quiet now, abandoned long before the Spanish came with their crosses and swords, long before America’s stars and stripes marched across this land. What drove them away? Drought, war, or something deeper?

The questions linger, but the road keeps pulling me forward.This is New Mexico’s heartbeat—a mix of bloodlines and languages, of Spanish ballads and Navajo chants, of mariachi trumpets and country guitars. It’s a love song and a battle cry, a contradiction that wears its scars proudly.

But even here, the churches loom. The adobe walls of the missions cast long shadows, their bells still calling the faithful to kneel. I think of the frailes who came here with their gospel and their greed, offering salvation with one hand and taking land with the other.

The road grows wider as I push toward the Four Corners. The land stretches wide, barren and beautiful, dotted with the occasional hogan or trailer, the windows glowing morse codes from the sun- A sputtering of hayfields and hungry horses. I think of the Diné, their prayers whispered to the Holy People, their stories woven into the constellations. I think of Changing Woman, of the sacred mountains that define their world.

But I also think of the uranium mines that scarred their land, the poisoned water, the treaties broken and forgotten. The promises that turned to ash.

Farmington rises like a mirage, a scatter of smog against the dark haze of change. The air smells different here, tinged with oil and dust, the echoes of industry humming faintly beneath the surface.

She is waiting for me, her text lighting up my phone: Buenos dias Bonita

I park next to her car, the engine ticking as it cools. The door opens, and there she is, her hair falling loose over her shoulders, her smile soft and familiar.

.

Her arms wrap around me, and for a moment, the weight of the road, of history, of everything, fades.Later, as we lie together in her small apartment, our bodies spent from love making with her head resting on my chest, I trace the scars of this place in my mind—the mountains carved by time, the rivers stolen and dammed, the people forced to bend and break.

But there is something else here too. Resilience. Resistance. A kind of love that holds on, even when the world tries to tear it apart.

She whispers something sweet, something soft and impermanent , and I feel it settle deep in my bones. The road between us is long, but tonight it feels small.

Outside, the stars watch, unblinking, as if they’ve seen this all before.

Category Archives: Blog

Taos Mesa

The rainbow touched down

‘somewhere in the Rio Grande,’

– Joy Harjo, She Had Some Horses

The Taos Mesa stretches wide, flat as a hand pressed against the earth, the sky leaning down close, listening.

Mesa near Taos, NM.

H a v e n © 2016

You feel it before you see it—that hum, low and constant, a sound that doesn’t ask for your understanding or permission. Some call it the Taos Hum, but the Pueblo elders say it’s something older, something the earth has always sung when no one was listening.

Out here, the sun is relentless, branding the mesa gold and red, scorching the dust into patterns only the eagles can read. But the nights—oh, the nights. The sky spills open, and the stars press down, sharp and infinite. It’s a cathedral of light, but not the kind that forgives.

The Pueblo people have watched these stars for a thousand years, their stories woven into the constellations. Tsídii, the bird spirit, flies between the stars, carrying prayers from earth to sky. Beneath these heavens, the Taos Pueblo still stand, the adobe breathing like a living thing, walls built from earth and sweat, from hands that knew how to shape the world.

The mesa is a place for the restless. Off-grid dreamers and dust-worn wanderers who build their makeshift kingdoms here, straw bale domes and reclaimed windows leaning into the wind. They come chasing freedom, chasing the horizon, chasing the ghosts of a West that never was.

But freedom here is a double-edged blade. The land gives and the land takes—water that hides deep underground, rattlesnakes that sleep in the shade of junipers, winter winds that howl like forgotten spirits.

The ones who stay learn to speak the language of this place. They learn that the earth here is unforgiving but alive, that every footprint is a promise, every breath a gamble.

Down in the pueblo, the stories stretch back to a time before time, when the Blue Lake gave life and the sacred mountains stood as guardians. The invaders came—Spanish conquistadors, American soldiers, missionaries with crosses sharp as knives—Drugs and broken families, but the people endured. They carried their history in songs, in dances, in the kiva fires that still burn.

In 1847, the U.S. flag rose over Taos Plaza, a symbol of a nation swallowing the land whole. But in the shadows of the plaza, the pueblo stood unbroken, its walls thick with defiance. When the rebellion came, it wasn’t just blood spilled on the dirt—it was centuries of resistance rising like smoke into the mountain air.

Now, the mesa is a collision of old and new. The Pueblo drummers still beat rhythms older than time, their hands calling the earth to listen. Meanwhile, out on the open plain, an Airstream trailer catches the light like a polished bone, a solar panel tilting toward the sun.

In the bars of Taos, neon signs flicker above wooden floors scuffed by boots and dreams. The jukebox hums with Johnny Cash and Los Lobos, their songs spilling out into the desert night, mixing with the wind, carrying pieces of America and something far older out onto the mesa.

You stand here, and the land speaks in contradictions. The history is carved deep, in petroglyphs hidden in basalt canyons, in the long shadows of the pueblo, in the stories the tourists never hear. But the future clings to this place too, a fragile thing balanced on solar power and second chances, on the hope that the earth will forgive us if we stay long enough to listen.

The mesa doesn’t belong to anyone, but it holds us anyway, for a moment, for a lifetime. Out here, under a sky so big it feels like it could swallow you whole, you start to understand.

The hum of the land is not a mystery to solve. It’s a reminder.

Of what came before.

Of what endures.

Of what we carry, whether we want to or not.

“Spiritual Apocalypse”: Settler Colonial Effects on the Changing Identities of Columbia River Indians

In 1988, during my time in middle school, my US history teacher delivered the news to the class that the Cascade/ Watala tribes residing along the Columbia River were no longer in existence because they did not have a reservation. This revelation struck a chord within me, as I felt deeply connected to the stories of my ancestors, both in flesh and spirit. In response to this declaration, I boldly asserted that we were not extinct, but rather transformed. This pivotal moment opened my eyes to a profound sense of self, one intrinsically intertwined with the land and the crucial presence of the Salmon, a keystone species. It was an identity forged out of defiance against the encroachment of settler colonialism and the reservation system that sought to uproot us from our sacred river. From the initial encounters with settlers to the present day, settler colonialism has irrevocably reshaped the physical and cultural landscapes along the Nch’i-Wanna (Columbia River).

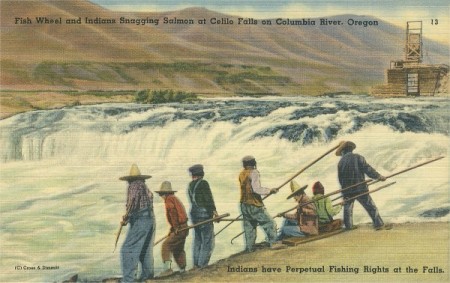

Throughout history, the Nch’i-Wanna has served as the ancestral homeland for various indigenous groups such as  the Watala/ Cascade, Wishram-Wasco, Klickitat, Yakima, Wanapum, and others. Despite their differences, these diverse cultures shared a deep connection with the river and its abundant Salmon. Ancient legends speak of Coyote bestowing the gift of Salmon upon the River People. The Salmon, in turn, carried the hopes and prayers of countless generations, swimming upstream to their birthplace at the Cascades Rapids (which gave the Cascade Mountains their name), passing through The Dalles straits, and continuing on to Wyam, also known as Celilo Falls, and beyond. Each spring, thousands would gather along the mighty river to celebrate the arrival of the first Salmon. They would sing songs, engage in trade, play stick games, and forge strong bonds of kinship. These vibrant cultures held a deep reverence for the natural world and had a profound sense of place. Traditional ceremonies like the Feather Religion were conducted to honor and express gratitude to the natural world. These cultural practices play a vital role in preserving the identity and heritage of the Columbia River Indians. They are a people who have chosen to live outside the confines of reservations and forced relocation, instead embracing the ways of their ancestors and the lifeways of the Big River.

the Watala/ Cascade, Wishram-Wasco, Klickitat, Yakima, Wanapum, and others. Despite their differences, these diverse cultures shared a deep connection with the river and its abundant Salmon. Ancient legends speak of Coyote bestowing the gift of Salmon upon the River People. The Salmon, in turn, carried the hopes and prayers of countless generations, swimming upstream to their birthplace at the Cascades Rapids (which gave the Cascade Mountains their name), passing through The Dalles straits, and continuing on to Wyam, also known as Celilo Falls, and beyond. Each spring, thousands would gather along the mighty river to celebrate the arrival of the first Salmon. They would sing songs, engage in trade, play stick games, and forge strong bonds of kinship. These vibrant cultures held a deep reverence for the natural world and had a profound sense of place. Traditional ceremonies like the Feather Religion were conducted to honor and express gratitude to the natural world. These cultural practices play a vital role in preserving the identity and heritage of the Columbia River Indians. They are a people who have chosen to live outside the confines of reservations and forced relocation, instead embracing the ways of their ancestors and the lifeways of the Big River.

Magic of Place written in stone.

identity. Starting with an overview of pre-contact life along the Columbia River, we will examine the culture of stories and place that informed the Ancestors space in the cosmos and how violently that changed after first contact. We will look at how that first contact was a sight unseen as pestilence decimated a People who had never known such a thing. Animist cultures who internalized the settler crisis on a spiritual level, creating a “spiritual apocalypse” across the Columbia River basin, where Dreamer Prophets arose with promises of deliverance from the settlers disease, violence and reservations that tore kinship ties apart. We will look at how the term “renegade Indian” became synonymous with the Columbia River Indian, and how resistance to settler colonialism continues to this day. We are not extinct, only transformed.

I. Pre-Contact to First Contact: Prehistoric Life on the Mid-Columbia River and the Coming Storms of Pestilence

“Long ago, when the world was young, all people were happy. The Great Spirit, whose home is in the sun, gave them all they needed. No one was Hungry, no one was cold. But after a while, two brothers quarreled over the land. The elder one wanted most of it, and the younger one wanted most of it. The Great Spirit decided to stop the quarrel. One night while the brothers were asleep he took them to a new land, to a country with high mountains. Between the mountains flowed a big river .” - Keeper of Fire, Bridge of the Gods Legend

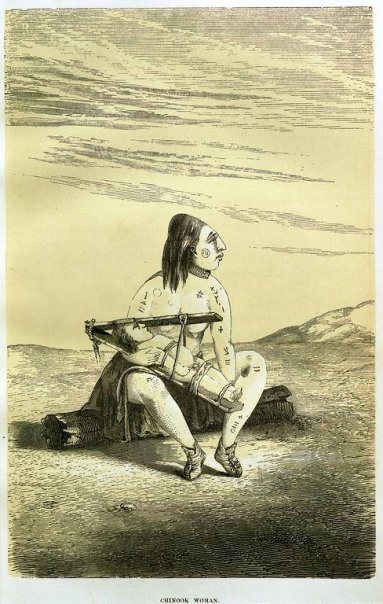

Paul Kane drawing of one of my Watala/ Chinook ancestors.

When Lewis and Clark made their westward voyage in 1804-05 they came across a Peoples who were already dealing with the effects of European contact with the spread of the smallpox epidemic among Pacific Northwest tribes in 1781. (Boyd, 2021) These epidemics swept through with a fury, altering the lives of thousands in a matter of a blink. It was endemic of what was ahead for the Columbia River Indians with the coming wave of settler colonialism. The epidemics began breaking down traditional tribal identities early on, cutting the population in about one half by 1801, yet the smallpox was just the beginning of the pestilence that would engulf Columbia River Indians. In the 1820’s, a Wasco prophet was reported to have had a vision that foresaw a day when many Indigenous People would “lay dead like driftwood along the shores of the [Big River].” (Fisher, 2011, p. 28) That vision became true just a few years later.

Fort Vancouver, HJ Ware, 1848

II. “Spiritual Apocalypse” and the Making of the Dreamer Prophets

Tsagaglalal (She Who Watches) is said to be a death mask, a warning of pestilence

In the first two contact-era Plateau epidemics (I770s and 18oo-i), there is much to indicate that illness and death were not blamed on outside contagion. The peoples of the region turned inward for explanation. Smallpox, and other serious diseases, signaled an imbalance or power struggle among the personal spirit partners that animated the spiritual universe of the Plateau. Smallpox was read as a spiritual crisis within Plateau societies, and the prophetic movements of the time were an attempt to stem that crisis. (Vibert, 1995, p. 4)

These prophetic movements were a grounding force within the Columbia River Indians cosmology. A way to bring sense to their changing world and align themselves with the wisdom of their elders, and to bring them back to life to help aid in restoration of traditional lifeways.

One of the earliest accounts of a plateau prophet traveling to the mid-Columbia region was that of Kaúxuma núpika, an indigenous transgender prophet living on the Columbia Plateau in the early nineteenth century. Kaúxuma núpika traveled the length of the Columbia River, prophesying a coming apocalypse and the destruction of Native people by epidemic diseases brought by Euro American settlers. (Crawford O’Brien, 2015, p. 4) These prophecies resonated strongly with the River People, and was the beginning of creating the renegade spirit that would define the Columbia River Indian character as the settler apocalypse sharpened its teeth. Although Kaúxuma núpika hit a chord with the People, it would not be until the prophet Smohalla and his Dreamer Religion would emerge in the 1850’s that the Columbia River Indian would claim a spiritual resistance to the settler apocalypse.

Chief Smohalla

III. “Nurseries of Civilization”: Diaspora, Reservations, and Resistance Along the Big River and the Emergence of the Columbia River Indian Identity.

“Where will we go? Where will we make our homes? If we lose our country what shall we do?”- William Chinook (Fisher, 2011, p. 37)

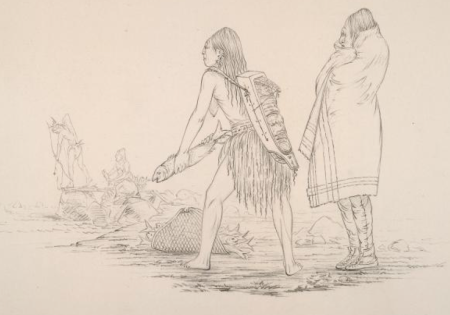

At The Dalles, George Catlin. 1850

Treaty Lands

Congress passed two pieces of legislation that unabashedly favored whites over Indians in the 1850’s. Starting in 1850 with the Oregon Donation Land Act, a piece of legislation that proclaimed that every adult male citizen could claim 320 acres from the public domain, and then with The Indian Treaty Act of 1850, which conveniently robbed the Indigenous People of their ancestral homelands and their removal to reservations to pave the way for a settler land grab.(Fisher, 2011, p. 40) These blatant racist policies of land theft and removal had no intention of honoring the cultural diversity of the Big River, only to further imaginary cultural lines that had nothing to do with the living cultures who were stuck in a desperate loop of survival. That survival was paramount to the Columbia River Indian- a survival that required them to live the life of their ancestors and to restore the land to its original pristine condition- just as Smohalla had instructed them. A land where the Salmon gifted all they needed.

Yakama Wars of 1855

The general view of Indigenous Peoples along the Big River by settlers was that there was no such thing as a good or neutral Indian. The conflicts that were arising around the PNW at the time would be viewed as an organized and cohesive resistance to settlers, which was only intensified by the newspaper’s propaganda at the time. This culture of fear would lead to much violence provoked by settlers towards Indians. Just like with much of the United States at the time, volunteer vigilante militia groups would use excessive violence with the Indigenous populations of the Oregon territory. The violence fueled fear among the population, forcing many to the confines of reservations in hopes of escaping it. (Fisher, 2011, p. 57-58) This dichotomy would fuel a division among Indians, a division of traitors vs. traditionalists. The injustices that occurred in the seizing of lands and falsifying of treaties during the 1850’s even made the Governor cringe, even recommending that a new one be written up and ratified with the tribes. This recommendation was all but ignored when the senate ratified all treaties written four years earlier in 1859. “Mid-Columbia Indians accepted or rejected the treaties on their own terms, and continued to think of themselves as members of extended families and autonomous villages rather than constituents of confederated tribes.” (Fisher, 2011, p. 59) The 1850’s was a signal post to a greater sense of identity and a loose designation as Columbia River Indians that will accumulate recognition in the decades to come. All the while, the Salmon came and the River ran its seasonal cycles.

*****************************************

Columbia River Indian Family at Celilo Falls

The reservation system was an attempt to keep Indians contained, but the seasonal lifeways and kinship ties that had been practiced for millenia would not keep River People contained. This autonomy and mobility would frustrate the powers that be, unable to know for sure how many “reservation Indians” they had “contained”. Agent James Wilbur would judge the “wandering vagrant Columbia River Indians” as folks who would only come to “subsist upon their more provident relatives.” (Fisher, 2011, p.65) The traveling, reservationless Columbia River Indian became known as “renegades”, always to live outside the lines of containment- but within the lines of their ancestral duties to the land and kin.

Settler colonial demands that had created the “spiritual apocalypse” a short 60 years prior had failed to deter old lifeways from extinction. We often speak of resilience here in “Indian Country”, not because we wish we had it, but because without it, we would not be here today. This resilience was the lifeblood of a people who lived tied to the cycles of a Big River- and with big hearts, would continue to resist and fight off the dragons so intent on destruction. The resilience of watching your people perish and still awake with love in your heart is strength beyond measure. This resilience, this strength, this resolve to exist along the Big River is the benchmark of what it meant and means to be a Columbia River Indian. This resolve would continue to get us targeted as “renegades”, and by the 1870’s would land us the official government correspondence title as “Columbia River Indians”. (Fisher, 2011, p.68)

IV. Conclusion

That pivotal day in 1988 woke me up to the complexity of our identities along the

Nch’i-Wanna which was formed out of the “spiritual apocalypse” of settler colonialism. An identity forged with resilience and resolve to keep the Ancestors memories alive and practice the old ways. Settler colonialism did not drive us extinct, it only transformed us- a transformation that continues to this day.

References

Boyd, R. (2021, December 10). The first epidemics: How disease ravaged Indigenous Northwest peoples. The Seattle Times. https://www.seattletimes.com/opinion/the-first-epidemics-how-disease-ravaged-indigenous-northwest-peoples/

Crawford O’Brien, S. (2015). Gone to the Spirits: A transgender prophet on the Columbia Plateau. Theology & Sexuality, 21(2), 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/13558358.2016.1215033

Fisher, A. H. (2011). Shadow tribe: The making of columbia river indian identity. University of Washington Press.

Hunn, E. S., & Selam, J. (1990). Nch’i-wána, “the big river”: Mid-Columbia indians and their land. University of Washington Press.

Vibert, E. (1995). “The natives were strong to live”: Reinterpreting early-nineteenth-century prophetic movements in the columbia plateau. Ethnohistory, 42(2), 197. https://doi.org/10.2307/483085

The Eternal Fire: Standing Rock and the (re)Awaking of Dreams

“My young men shall never work; men who work can not dream, and wisdom comes in dreams.” —Smohalla

In the still water quieted by pale dams, there is a whisper of dreams. A whisper that used to drive and propel hope through the changing landscape of “Indian Country” during the 1800s. In a time of great death and cultural genocide, many prophets spoke of dreams. Dreams that would bring the old ways back to the people.

Up River, Back Home

Dreams were a fabric in which to weave stories of resilience and hope. These dreams kept the people fed and brought prophecy. The dreamer brought the people a sense of peace that one day their Ancestors would rise again from their untimely deaths brought about from settler colonialism. These are old dreams dressed in new clothes, a way for the Ancestors to keep speaking to us.

Many felt that a dream led them to the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in 2016 to fight the Dakota Access Pipeline, including me. Many spoke of how it felt like their Ancestors had nudged them awake, as if the Earth was rising in a chorus of resistance to a machine that is hell-bent on destruction and greed. I recently read a Time magazine article about Standing Rock, that begins:

“Almost everyone who came to Standing Rock repeated the same legend. Someone, maybe Crazy Horse, had made a prophecy a long time ago—probably in the late 1870s—about the looming destruction of the planet.”

And that is exactly what called me there.

The liminal essence of dreaming was the fabric of everyday conversation in camp. From the morning prayers at the Sacred Fire to the frontlines of resistance, prophecy was on everyone’s lips. But to me, this was more than an Awakening. It was a confirmation that my dreams have always been telling me such things. Things I was beginning to finally understand.

********************************************

I was a young six-year-old; she was a timeless maiden. She changed my life! So clear the memory. So clear the vision. Awaken, the plume of ash on the horizon, safe near my parents. Several nights before, the whole house shook, the earth quaked, and I remember my curious thoughts: How did the Earth shake? What caused it? At that age, I was more of a scientist than an artist. But something changed in me, and my dreams would never be the same.

May 18th, 1980

I was beginning to understand what my grandmother was telling me. She talked about the Bridge of the Gods, and the Mountains of Fire, and how the brothers Wyeast¹ and Pahtoe² would battle and argue for the love and admiration of Loowit³, or how Coyote made the N’ch-iwana⁴, and the stories of Thunderbird. She would talk about the little people, the Wah-Tee-Tahs, how they would lure you in with their mischief, all the supernatural stories of ghosts, and old burial sites, and my family’s struggle to make meaning out of the changing world around them. She would tell me these stories and end them with, “But we don’t believe like that anymore.”

It was true. She and so many members of my family stopped believing in the old stories and ways of our tribe and traded them in for a fundamentalist, vengeful god. When I was six and saw the timeless maiden Loowit blow her top on May 18, 1980, the old stories awoke in me. I wanted to know more about the old ways and how to practice them, but all I had to go off of were stories. And then the dreams came.

I used to pray, even if the sounds echoed into empty space. I had some faith that those words would reach some distant star, and portals would open up in the night sky. But instead I would dream. I would dream until I forgot what I was dreaming about. What was the reason for the journey? I often find the journey is the only thing that keeps me still most times, nodding off to the narcotic rhetoric of the modern age. It is in these journeys I meet my guides, who, with unforeseen hands, move the air of the fates in and out of existence. Coyote always seems to wake me up right before the climax. I was being shown a new way, a new story, if only I would listen.

Home Guard on the Columbia, by Benjamin A Gifford (1899) (photo- courtesy The Valley Library, Oregon State University)

The dream was this: Coyote was coming down the N’ch-iwana. He would stop at the lodges, rip open the doors, and yell, “Get up! The Salmon need you!”

He would stop at the fishing platforms dotted along the banks, yelling, “Stay alert! The Salmon are leaving! They need you!”

Everyone was bewildered.

“What is he talking about? Crazy trickster. He is always up to something!”

He would say back to them, “Get up! The Salmon need you!” Back and forth up the river he would go, telling anyone, whether they wanted to hear it or not, “Stay alert! The Salmon need you!”

I awoke to the feeling of sweat upon my brow, the dream resting on the tip of my tongue, goosebumps skimming my flesh, and my heart heavy with the message. “Get up! The Salmon need you!” I knew what was being asked of me; I felt it in my tired bones. It was the morning of October 26, 2016.

I was still sore and relearning the sacrament of swallowing. Just a week prior, I had a surgery on my esophagus to help cure a disease that nearly took my life. A month before my surgery, I had to live with a feeding tube in my esophagus, so it could start its healing process. I laid in bed, watching as the standoff at Standing Rock was unfolding. I felt a calling to be there, to help my cousins in North Dakota fight for their Sovereignty, and for the Mni Wiconi⁵, but was certain I would have to help from afar. On that cold October morning, I knew it was time to go.

I felt the old trickster’s words resonate in my heart. Indeed, the Salmon needed us. Since the first contact, Coyote had seen so much: from a river so fat with Salmon you could walk across it on top of their backs, to a silent dragon stuck in the gold pockets of a civilization determined to save a “savage” from its blasphemous ways. The roar of Wyam⁶ had grown silent to Coyote. And the Salmon, who fueled the stories and myth of old, were becoming ghosts before the spawn.

Celilo Falls, post card. ca. 1930

Many of us River People speak about still hearing those waters fall, like a longing at the doors of our dreams or a remembering that we know in the beating of our hearts. Each pump a drum of longing to be home amongst the joyful jumping of Salmon. A familiar smoke drifting from shacks holding old stories, the repeating patterns of metaphor, and the sound of Echoes of Water Against Rocks.

After the dream, I knew I had to go and stand with others who were standing against these mythical beasts. The sleeping dragon had awoken to the slithering black snake of the Dakota Access Pipeline. I packed my things and headed to Lakota country.

In Lakota prophecy, Zuzeca Sape is the black snake that comes into the land, breeding division and destruction in its path. I had heard this prophecy before from my Aunty Teri, who had learned much of the Lakota’s stories from her early activism with the American Indian Movement in the early 1970s. But only now were some of the meanings becoming apparent. Many tribes of People talked about the NoDAPL movement being Zuzeca Sape, and many People talked about their dreams.

Backwater Bridge, Cannonbal, ND, NoDapl, November 8, 2016, Photo by Author

We left the Volcanoes and Rivers of my homeland and began our trek across mountains and endless plains in a van packed with donated supplies gathered in the haste of a great battle. We traveled excitedly and quietly. I was still finding it hard to swallow from my surgery. I felt weak, but determined. My words sat in my guts, and the drums of Pow-Wow CDs played a battle hymn to our coffee-fueled mission to the Oceti Sakowin.

“Get up! The Salmon need you!”

With the dream dancing in my head, we pulled into camp. Before us stood an encampment of so many others that had heard the call to show up and stand. We quickly set up our camp, got donations to their proper places, and made our way to the Sacred Fire of the Oceti Sakowin. I walked to the fire in the middle of a large circle of smiling faces, some with tears in their eyes—tears of joy and from the tear gas that had been poured upon the People with impunity. There was an Elder tending the Fire, his hand outstretched to mine as he handed me the tobacco to put into the flames. Our eyes locked, and as the tears began to pour down my thin face he said, “Welcome home, brother.” I prayed harder than I had ever prayed before as I walked clockwise around the Fire and put my offering into the thick smoke. The marriage of dream and prayer, complete in union.

I had still not eaten a full meal since my surgery a week prior, and the protein shakes I had brought were beginning to run out. I had a deep hunger that had not been fed since I became ill four years prior, a hunger that was ravenous and tired. We decided to head to one of the many soup kitchens serving food, and as we slowly made our way through the line, we talked to folks that had been in camp since the beginning of the NoDAPL resistance. There were Lakota cousins, Cherokee cousins, Blackfeet cousins, Navajo cousins, all the many tribes of Turtle Island in one place, sharing stories, laughing, and full of love. I was handed a plate by a Lummi Grandmother from the homelands who asked me if I had just arrived.

“Yes,” I said, “a few Cowlitz Cousins and I just pulled into camp a few hours ago.”

She hugged me with a stern grasp and whispered, “Welcome Cousin, we have Salmon from our homeland, please enjoy.”

My plates were filled by kind servers, all telling us, “Welcome, Mni Wiconi!” Generous portions of Salmon, huckleberries, and fry bread were laid upon our plates with love. We walked outside the serving tent and looked for a place to sit and found some Northwest Natives that had brought the fish for the People.

“Where is the Salmon from?” I asked one of the younger cousins.

“Oh, yeah, this Salmon came from the N’ch-iwana.” he replied in a thick rez accent.

“I believe most of this catch came from the Celilo Falls area.”

Les Brown photo. ©2012

My neck hairs rose like porcupines as I edged the first bite to my mouth, whispering beneath my breath a Prayer of thanks to the Salmon People. I took a bite, and, swirling the pink sweet meat in my mouth, watering and eager, I swallowed. I could feel the medicine make its way down the new tube the surgeon had made just a week earlier, each movement wiggling in anticipation. It landed in my empty stomach, as a choir of sensations flooded my senses. Bite after bite, prayer after prayer, I was full as if for the first time. I was home. I was no longer dreaming.

“Get up! Stay Alert! The Salmon need you!”

Masi Coyote.

Mni Wiconi!

(This was originally published by Beyond the Margins, Oregon Humanities. All rights reserved by Author, Si Matta)

The Leather Bound Journal

“Magic is afoot, God is alive.”- Buffy Sainte-Marie

Her dreams reassuringly whisper in journals made of leather. The engraved cover

gathering dust in the creases of her ancestors’ knot work; mythology and aesthetics that render

the heart through time. The company of rocks, feathers, and photos stand astute as altars to

memories through the halls of nostalgic flowers, dried and pressed.

A richly painted sunset grow’s silent in sleeping eyes, as if preparing herself for ritual,

she lays the journal on the tiered nightstand. The bond of dreams now past, yet ever present in

the great rites of a secret society. Curious shadows drape the night, and words fall from her

sleeping lips. Will those words find their place engraved in the leather bound journal of her

heart?

The delinquent voices sing the praise of night’s great sermon, ushered forth through pens

whose ink refuses to run dry. The extravagant want of knowing sits in a curious corner, the

holder of shadows, and fields of exhausted dreams. I wonder what she writes, as she scribes the

visions of a reluctant Sage? What great prophecy does the night entail in these pages lined with

words? What monsters lay slain at the feet of her Gods?

In the high noon of a winter’s day, when the light strains through the milky white

shutters, and the bustle of waking life dances the dance of routine, the old journal sits. What

silent conversations must happen in these churches of dust? Do the rocks tell stories about how

they were born of Volcano, and have lived to witness the anthropocene? Does the Phoenix

silently gather back their dormant flaming feathers? Do the flowers speak of their once great

pageantry, before being pressed and fitted into their eternal form? Does her father escape his

photographic prison to share stories of his daughter’s great feats? The totemic dragonfly lamp

stands guard atop its utilitarian box made mountain, draped in cloth and stone made coasters,

ready to sound the alarm of the creator; an ushering of quiet as not to give their animism away.

The tapping of the pens scribed great scripture, a drum that eternally beats in time with

her heart. A calligraphy of soul draped in esoteric symbols only meant for her sacred eyes; span

the enormity of dream, nightmare, and waking life. It tethers her to the divine, and unravels the

great inferno. There must be so much beneath those covers made of leather. Seas upon seas of

tear drenched papers brought from the clouds of grief and sadness, or the suns of joy and peace.

The stories of grandbabies and daughters whose hearts have hers, and blood pumps forth the

changing face of family. All these stories wrapped and tidy, made from the love of a well lived

life. All the stories where the beast is slain with great bravery and skill, as not to disturb her

loves from sleep. The holder of the flame, the Phoenix from the ashes; a journal.

2020 Vision(s)

If it should happen you wake up and Armageddon has come, lie still.

― William Edgar Stafford

Last night I

saw the

moon

slip

in

and out

of golden light.

A flame burnt

ember of

gas

exploding

in my eyes.

Watching the end

of the world

no longer

feels

so

dramatic.

© Si Matta

The Birds Whispered My Name

Some birds are not meant to be caged, that’s all.- Stephen King

The birds whispered my name,

As I fidgeted on a cold chair,

Learning of a god dressed in thorns.

As they talked in righteous dictation,

I would pull thorny brambles from dirty hands-

Finding god in the splinters.

I remember how the rain tasted-

Dry in safe beds made from synthetic fibers.

Yet I could hear the birds whisper my name,

Telling me stories,

We forgot to tell ourselves.

© Si Matta

Fire

Each of us is born with a box of matches inside us but we can’t strike them all by ourselves― Laura Esquivel

I use to dream,

but my well

has ran dry.

Like cottonmouth.

I often cough

on words and

pass the torch.

A flame.

© Si Matta

Sinew

Never lost/ Fading slowly to Silence/ By infinite degrees”

― Ashim Shanker

The sinew of

the moment led

us to this

leather of silence.

Sometimes I forget

your name, but remember

the taste.

A distant drum-

Your heart.

© Si Matta

Toivo Land, WA 98648

“Hope is the thing with feathers

That perches in the soul

And sings the tune without the words

And never stops at all.” – Emily Dickinson

~

There are numbers zipped up in code that distinguish a place. A place where the mailman sometimes drives a mile or more to the next box; markers upon a black sea of asphalt, gravel and rain. Toivo lived here, amongst the mapleway and dirt trails- snags of trees swaying in the wind. A psithurism cathedral, with halls that echoed Finnish Polkas in a land of make believe. My Grandfather came from an old world, yet made a new one in the mossy twigs of 98648.

I am the oldest of 10 grandchildren, and arrived into a world filled with imagination and music. My grandfather played the accordion, spoke Finnish when drinking with his brothers and sisters, and loved to tell good stories. My oldest memories are set to the soundtrack of joy, laughter, and the Chicken Dance. Gramps had instruments in every corner and nook- amongst the dusty wisps of paper scrolled upon with poems, music, and blueprints for building. His hands were always inventing something new. When I was 9, he invented Toivo Land.

Toivo was an imaginary friend he made out of sawdust flesh, dressed in cover-alls, and who wore a face of permanent marker drawn upon a milk jug. Toivo always sat on an old Ford tractor that was rusty and splintered (unless he was out and about with the Toivo Land Band.) Toivo was a Magician, and like the Wizard of Oz, Toivo plowed a yellow brick road dotted with hand painted signs, and paved with the falling leaves of Maples, Oak, and Fir. A network of discovery that spanned 3 acres, and a lifetime. Toivo was always busy- this was Toivo’s land.

Toivo: 1) Finnish toivo = ‘hope’, ‘wish’, ‘desire’ 1 a) … with an older meaning ‘faith’, ‘trust’, ‘promise’

(Photo of Toivo Land Band @ Skamania County Fair Parade, Stevenson, WA. 98648 , cir. 1984)

~~

The faint sound of Polka seeping from old cassettes keeps time with the machines monitoring his breathing. His heart beats sporadic metronomes to his Covid-19 fever dreams. His fingers fold in on themselves- clutched and cold. It has been awhile since he has held the weight of billows and keys strapped upon his stern shoulders. He is quiet and ready- ready to make music again.

“Thank you,” I sob a hard sentence, stuck in my throat made of his flesh, “thank you Grandpa for always being there, and making our lives magic, and filled with love.”

“Thank you Grandpa for Toivo!”- I strain the words between tears that fall upon my pandemic shield made of plastic.

We lock a gaze of Finnish silence, the kind of silence filled with the solidarity of *Sisu. A stoic tear moves its way down his ageless face of wisdom, and with a side quiet smile, he says:

“It is all I could have hoped for!”

“It is all I could have hoped for.”

———————————————————————————————————————

* Sisu is a Finnish concept described as stoic determination, tenacity of purpose, grit, bravery, resilience, and hardiness and is held by Finns themselves to express their national character. It is generally considered not to have a literal equivalent in English.