“My young men shall never work; men who work can not dream, and wisdom comes in dreams.” —Smohalla

In the still water quieted by pale dams, there is a whisper of dreams. A whisper that used to drive and propel hope through the changing landscape of “Indian Country” during the 1800s. In a time of great death and cultural genocide, many prophets spoke of dreams. Dreams that would bring the old ways back to the people.

Up River, Back Home

Dreams were a fabric in which to weave stories of resilience and hope. These dreams kept the people fed and brought prophecy. The dreamer brought the people a sense of peace that one day their Ancestors would rise again from their untimely deaths brought about from settler colonialism. These are old dreams dressed in new clothes, a way for the Ancestors to keep speaking to us.

Many felt that a dream led them to the Standing Rock Sioux Reservation in 2016 to fight the Dakota Access Pipeline, including me. Many spoke of how it felt like their Ancestors had nudged them awake, as if the Earth was rising in a chorus of resistance to a machine that is hell-bent on destruction and greed. I recently read a Time magazine article about Standing Rock, that begins:

“Almost everyone who came to Standing Rock repeated the same legend. Someone, maybe Crazy Horse, had made a prophecy a long time ago—probably in the late 1870s—about the looming destruction of the planet.”

And that is exactly what called me there.

The liminal essence of dreaming was the fabric of everyday conversation in camp. From the morning prayers at the Sacred Fire to the frontlines of resistance, prophecy was on everyone’s lips. But to me, this was more than an Awakening. It was a confirmation that my dreams have always been telling me such things. Things I was beginning to finally understand.

********************************************

I was a young six-year-old; she was a timeless maiden. She changed my life! So clear the memory. So clear the vision. Awaken, the plume of ash on the horizon, safe near my parents. Several nights before, the whole house shook, the earth quaked, and I remember my curious thoughts: How did the Earth shake? What caused it? At that age, I was more of a scientist than an artist. But something changed in me, and my dreams would never be the same.

May 18th, 1980

I was beginning to understand what my grandmother was telling me. She talked about the Bridge of the Gods, and the Mountains of Fire, and how the brothers Wyeast¹ and Pahtoe² would battle and argue for the love and admiration of Loowit³, or how Coyote made the N’ch-iwana⁴, and the stories of Thunderbird. She would talk about the little people, the Wah-Tee-Tahs, how they would lure you in with their mischief, all the supernatural stories of ghosts, and old burial sites, and my family’s struggle to make meaning out of the changing world around them. She would tell me these stories and end them with, “But we don’t believe like that anymore.”

It was true. She and so many members of my family stopped believing in the old stories and ways of our tribe and traded them in for a fundamentalist, vengeful god. When I was six and saw the timeless maiden Loowit blow her top on May 18, 1980, the old stories awoke in me. I wanted to know more about the old ways and how to practice them, but all I had to go off of were stories. And then the dreams came.

I used to pray, even if the sounds echoed into empty space. I had some faith that those words would reach some distant star, and portals would open up in the night sky. But instead I would dream. I would dream until I forgot what I was dreaming about. What was the reason for the journey? I often find the journey is the only thing that keeps me still most times, nodding off to the narcotic rhetoric of the modern age. It is in these journeys I meet my guides, who, with unforeseen hands, move the air of the fates in and out of existence. Coyote always seems to wake me up right before the climax. I was being shown a new way, a new story, if only I would listen.

Home Guard on the Columbia, by Benjamin A Gifford (1899) (photo- courtesy The Valley Library, Oregon State University)

The dream was this: Coyote was coming down the N’ch-iwana. He would stop at the lodges, rip open the doors, and yell, “Get up! The Salmon need you!”

He would stop at the fishing platforms dotted along the banks, yelling, “Stay alert! The Salmon are leaving! They need you!”

Everyone was bewildered.

“What is he talking about? Crazy trickster. He is always up to something!”

He would say back to them, “Get up! The Salmon need you!” Back and forth up the river he would go, telling anyone, whether they wanted to hear it or not, “Stay alert! The Salmon need you!”

I awoke to the feeling of sweat upon my brow, the dream resting on the tip of my tongue, goosebumps skimming my flesh, and my heart heavy with the message. “Get up! The Salmon need you!” I knew what was being asked of me; I felt it in my tired bones. It was the morning of October 26, 2016.

I was still sore and relearning the sacrament of swallowing. Just a week prior, I had a surgery on my esophagus to help cure a disease that nearly took my life. A month before my surgery, I had to live with a feeding tube in my esophagus, so it could start its healing process. I laid in bed, watching as the standoff at Standing Rock was unfolding. I felt a calling to be there, to help my cousins in North Dakota fight for their Sovereignty, and for the Mni Wiconi⁵, but was certain I would have to help from afar. On that cold October morning, I knew it was time to go.

I felt the old trickster’s words resonate in my heart. Indeed, the Salmon needed us. Since the first contact, Coyote had seen so much: from a river so fat with Salmon you could walk across it on top of their backs, to a silent dragon stuck in the gold pockets of a civilization determined to save a “savage” from its blasphemous ways. The roar of Wyam⁶ had grown silent to Coyote. And the Salmon, who fueled the stories and myth of old, were becoming ghosts before the spawn.

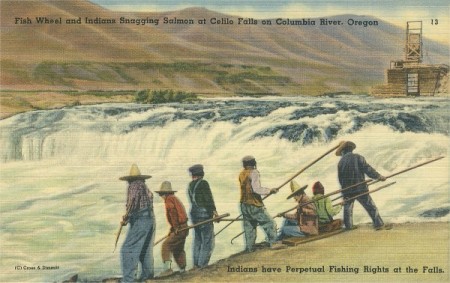

Celilo Falls, post card. ca. 1930

Many of us River People speak about still hearing those waters fall, like a longing at the doors of our dreams or a remembering that we know in the beating of our hearts. Each pump a drum of longing to be home amongst the joyful jumping of Salmon. A familiar smoke drifting from shacks holding old stories, the repeating patterns of metaphor, and the sound of Echoes of Water Against Rocks.

After the dream, I knew I had to go and stand with others who were standing against these mythical beasts. The sleeping dragon had awoken to the slithering black snake of the Dakota Access Pipeline. I packed my things and headed to Lakota country.

In Lakota prophecy, Zuzeca Sape is the black snake that comes into the land, breeding division and destruction in its path. I had heard this prophecy before from my Aunty Teri, who had learned much of the Lakota’s stories from her early activism with the American Indian Movement in the early 1970s. But only now were some of the meanings becoming apparent. Many tribes of People talked about the NoDAPL movement being Zuzeca Sape, and many People talked about their dreams.

Backwater Bridge, Cannonbal, ND, NoDapl, November 8, 2016, Photo by Author

We left the Volcanoes and Rivers of my homeland and began our trek across mountains and endless plains in a van packed with donated supplies gathered in the haste of a great battle. We traveled excitedly and quietly. I was still finding it hard to swallow from my surgery. I felt weak, but determined. My words sat in my guts, and the drums of Pow-Wow CDs played a battle hymn to our coffee-fueled mission to the Oceti Sakowin.

“Get up! The Salmon need you!”

With the dream dancing in my head, we pulled into camp. Before us stood an encampment of so many others that had heard the call to show up and stand. We quickly set up our camp, got donations to their proper places, and made our way to the Sacred Fire of the Oceti Sakowin. I walked to the fire in the middle of a large circle of smiling faces, some with tears in their eyes—tears of joy and from the tear gas that had been poured upon the People with impunity. There was an Elder tending the Fire, his hand outstretched to mine as he handed me the tobacco to put into the flames. Our eyes locked, and as the tears began to pour down my thin face he said, “Welcome home, brother.” I prayed harder than I had ever prayed before as I walked clockwise around the Fire and put my offering into the thick smoke. The marriage of dream and prayer, complete in union.

I had still not eaten a full meal since my surgery a week prior, and the protein shakes I had brought were beginning to run out. I had a deep hunger that had not been fed since I became ill four years prior, a hunger that was ravenous and tired. We decided to head to one of the many soup kitchens serving food, and as we slowly made our way through the line, we talked to folks that had been in camp since the beginning of the NoDAPL resistance. There were Lakota cousins, Cherokee cousins, Blackfeet cousins, Navajo cousins, all the many tribes of Turtle Island in one place, sharing stories, laughing, and full of love. I was handed a plate by a Lummi Grandmother from the homelands who asked me if I had just arrived.

“Yes,” I said, “a few Cowlitz Cousins and I just pulled into camp a few hours ago.”

She hugged me with a stern grasp and whispered, “Welcome Cousin, we have Salmon from our homeland, please enjoy.”

My plates were filled by kind servers, all telling us, “Welcome, Mni Wiconi!” Generous portions of Salmon, huckleberries, and fry bread were laid upon our plates with love. We walked outside the serving tent and looked for a place to sit and found some Northwest Natives that had brought the fish for the People.

“Where is the Salmon from?” I asked one of the younger cousins.

“Oh, yeah, this Salmon came from the N’ch-iwana.” he replied in a thick rez accent.

“I believe most of this catch came from the Celilo Falls area.”

Les Brown photo. ©2012

My neck hairs rose like porcupines as I edged the first bite to my mouth, whispering beneath my breath a Prayer of thanks to the Salmon People. I took a bite, and, swirling the pink sweet meat in my mouth, watering and eager, I swallowed. I could feel the medicine make its way down the new tube the surgeon had made just a week earlier, each movement wiggling in anticipation. It landed in my empty stomach, as a choir of sensations flooded my senses. Bite after bite, prayer after prayer, I was full as if for the first time. I was home. I was no longer dreaming.

“Get up! Stay Alert! The Salmon need you!”

Masi Coyote.

Mni Wiconi!

(This was originally published by Beyond the Margins, Oregon Humanities. All rights reserved by Author, Si Matta)

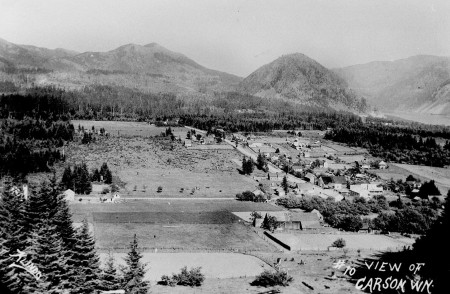

Growing up, I could see Wind Mountain directly from my bedroom window. I would get lost in daydream, which is a pretty common occurrence for me, and wonder how my ancestors revered and interacted with this landscape. What was it about this mountain that made it holy or sacred? Was it because of it’s stand alone features in the middle of the Cascade Mountain range? Was is it because of the sacred mineral waters that bubbled and boiled in her shadows? Or, was it because it could have been where the actual land bridge, known as the Bridge of the Gods, could have crossed the mighty river? – And Who had the first Vision on her lofty peak? Was it Coyote?

Growing up, I could see Wind Mountain directly from my bedroom window. I would get lost in daydream, which is a pretty common occurrence for me, and wonder how my ancestors revered and interacted with this landscape. What was it about this mountain that made it holy or sacred? Was it because of it’s stand alone features in the middle of the Cascade Mountain range? Was is it because of the sacred mineral waters that bubbled and boiled in her shadows? Or, was it because it could have been where the actual land bridge, known as the Bridge of the Gods, could have crossed the mighty river? – And Who had the first Vision on her lofty peak? Was it Coyote?