Up to the age of twenty-five my grandmother thought her name was Abbie L. Weiser. Then she met her father and found out her name was really Lucy Gerand, which at least explained the middle initial. He had chosen that name after his own, Louis Gerand, but she had no way of knowing that.

Abbie Lucy Weiser Gerand Reynolds Estabrook

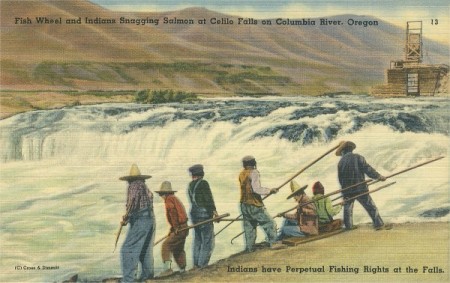

(Weiser was the name of Louis’s step-father so maybe he carried that last name at times; for sure his mother did.) Louis left the Columbia River Gorge area two years after his daughter’s birth which was at Mars Landing (Skamania) in February 1887, when Washington was still a territory.

Abbie’s mother was Mary Stooquin, a Cascade Indian living along the Columbia River in southern Washington. She was also known by the Indian name Kalliah. Mary was born about 1854, the daughter of one of the Cascade headmen, Tumulth (also known as Tomalch or Tomalt, among other spellings) and one of his several wives, Kisanua/“Susan.” As a child Mary would have been known as Mary Tumulth or Tomalch. Mary remembered her father’s hanging two years after her birth by the rising young Cavalry officer, Phil Sheridan, for participation in the 1856 Indian uprising at the Cascades, a major portage site on the Columbia. The family story is that Tumulth was not at the Cascades before the attack but came up from his winter village downriver to try to negotiate between the parties. Sheridan did not give him a chance to intervene.

Louis Gerand was half French and half Cowlitz Indian born at Ft. Vancouver in 1848. His father was likely a fur company employee and his mother was

Grandma Kalliah and Abbie.

the Cowlitz woman known as Skloutwout. Louis had an allotment on the Warm Springs Reservation in central Oregon where many Indians from the south side of the Columbia had been consolidated. While he was not from that area, allotments were given to a broader group of Indians to justify a larger-sized reservation. The short-term liaison between Louis and Mary was not uncommon in those days when the lives of the Natives had been so disrupted. In fact, he had another wife at the time, Eliza, who was at Warm Springs. Louis and Eliza had no surviving children, making Abbie his only heir. Abbie’s paternity was the subject of a successful lawsuit a few years after his death that allowed her to inherit her father’s reservation land.

Mary herself had a number of husbands and is, therefore, known by various names as an adult: Mary Stooquin, Mary Weiser, Mary Wilwy-itit, Mary Henry. Actually, Wilwy-itit and Henry were one person, Henry Wilwy-itit, probably a Wishram Indian. Once an official asked Mary her husband’s name and she replied, “Henry.” So he wrote down “Mary Henry” not knowing that was but a first name. Her obituary lists her name as “Mary Weiser.” Within our family, we refer to her as Mary Stooquin, wife of Johnny Stooquin, since that’s the name our mother Kathleen used for her grandmother.

Though an Indian, my grandmother Abbie was raised mostly among white people and taught their ways as the Cascade community had largely disappeared. The tribe suffered tremendously in the disease epidemics of the 19th century, not to mention the loss of lives in the 1856 uprising known as the “Cascades Massacre.” As a consequence of that fight Sheridan hanged eight other Native men along with Tumulth. A number of men of the tribe did escape with the Yakamas and Klickitats who had stirred up the trouble and over time some families settled on the Yakama, Warm Springs and Grand Ronde reservations.

The Cascade Indians who remained in their homeland to try to maintain their ties to the area had little choice but to assume a life on the fringes of white society, especially those just growing up as were Mary and her sisters. All three of them took husbands who, if not all white, were of mixed blood because there were almost no Native males available as spouses.

Mary Stooquin gained some standing among the whites as evidenced by her being awarded a government contract as a carrier for mail brought by boat from Portland to Cascades, the old county seat. Not only that, but she received a special 160-acre grant of land in trust from the federal government in 1893 in the Skamania area for acreage she had been living on for many years. This land grant may have been in connection with a negotiation between the remaining Cascade Indians and the government in 1892 over loss of territory and fishing rights. Mary was a party to that unsuccessful petition.

Mary Stooquin gained some standing among the whites as evidenced by her being awarded a government contract as a carrier for mail brought by boat from Portland to Cascades, the old county seat. Not only that, but she received a special 160-acre grant of land in trust from the federal government in 1893 in the Skamania area for acreage she had been living on for many years. This land grant may have been in connection with a negotiation between the remaining Cascade Indians and the government in 1892 over loss of territory and fishing rights. Mary was a party to that unsuccessful petition.

One of the things that association with whites taught was the value of education. Mary saw to it that her girls, Amanda and Abbie, went to school as long as they could, even if it meant rowing across the Columbia River to reach the schoolhouse. The story is that Abbie loved school. She went all the way through elementary and when she got to eighth grade, repeated it three times. The teacher finally told Abbie that she had already learned everything the teacher had to offer. Although not a result of school learning, Abbie would be considered tri-lingual by modern standards as she spoke English, Kiksht (the difficult native language of the mid-Columbia area) and Chinook jargon (the trade language used among tribes and whites throughout the Pacific Northwest, British Columbia and Alaska). Abbie always had a love for reading, in later years subscribing to both the Portland and Stevenson newspapers and numerous national magazines of the day such as Life, Good Housekeeping and True Story. Frank Estabrook, her second husband, was illiterate. For him she ordered Popular Mechanics so he could study the photos and get ideas for his projects.

When Abbie and her older half-sister Amanda were grown, they, too, married white men. Abbie’s husband was Morris Reynolds, a Danish American, whom she met while he was working on the railroad. He was handsome and charming but turned out not to be one to provide a consistent living for his wife and children. He preferred the city life in Portland and spent a lot of time there drinking and gambling with his brother. Abbie was attractive to him because she was wealthy in a way—she had some horses and half of the 160 acres she and her sister had inherited from her mother. Morris spent his money and then borrowed from his mother. Eventually Abbie’s portion of the land that had been Mary Stooquin’s at Skamania passed into the hands of Morris’s mother in repayment of his debts to her.

When Abbie and her older half-sister Amanda were grown, they, too, married white men. Abbie’s husband was Morris Reynolds, a Danish American, whom she met while he was working on the railroad. He was handsome and charming but turned out not to be one to provide a consistent living for his wife and children. He preferred the city life in Portland and spent a lot of time there drinking and gambling with his brother. Abbie was attractive to him because she was wealthy in a way—she had some horses and half of the 160 acres she and her sister had inherited from her mother. Morris spent his money and then borrowed from his mother. Eventually Abbie’s portion of the land that had been Mary Stooquin’s at Skamania passed into the hands of Morris’s mother in repayment of his debts to her.

It’s plain that the marriage between Abbie and Morris was passionate but tumultuous. There were times when she kept a shotgun and would not let Morris into the house. Other times she threatened to take her life with a knife and Morris had to wrestle it away from her on the floor. The rugged life of a logging camp in itself did not improve matters.

Of the eight children Abbie bore between 1908 and 1920, only five survived infancy. In that era many babies succumbed to influenza and pneumonia. Her surviving children were Charles Raymond known as “Ray” (born 1908), Mary (1910), Lucille (1913) and Kathleen (1914), my mother. Son Johnny (1920) drowned in the Little White Salmon River when he was 12 years old. Two of the girls had Indian names which may have been given to them by Abbie’s aunt Virginia Miller. Lucille’s was Kwaiak, a name also associated with Virginia. Kathleen’s was Chaiminigh whose meaning we don’t know. (Note that these are phonetic spellings so might vary if seen elsewhere.)

About 1919 it did finally appear that Morris was ready to settle down. Abbie’s Native enrollment was with the Yakama Tribe so the family went to Toppenish where Abbie had relatives. They set out to run a hotel. Things were fine until Morris sent for his mother to come help. She tried to get Abbie to change only one of the sheets on a bed at a time. But the customers didn’t like that, so the hotel venture lasted only another two weeks. The family moved back to Cascades and in a few months Morris went to Warm Springs to build a house on the property that Abbie inherited from her father. The house was nearly complete and he was about to send for the family when he took sick, returned home and quickly died. Morris was only thirty-four years old. Abbie always thought he had been poisoned, possibly by his half-sister who felt she had a right to the property. An alternative theory is that he contracted Rocky Mountain spotted fever from a tick bite. One memento that Abbie kept of the connection to the Warm Springs Reservation was a juniper tree in the front yard of her Stevenson home. The tree still stands on that property. It was probably brought from Warm Springs as a seedling long ago, a dryland evergreen planted into one of the rainiest counties in Washington.

About 1919 it did finally appear that Morris was ready to settle down. Abbie’s Native enrollment was with the Yakama Tribe so the family went to Toppenish where Abbie had relatives. They set out to run a hotel. Things were fine until Morris sent for his mother to come help. She tried to get Abbie to change only one of the sheets on a bed at a time. But the customers didn’t like that, so the hotel venture lasted only another two weeks. The family moved back to Cascades and in a few months Morris went to Warm Springs to build a house on the property that Abbie inherited from her father. The house was nearly complete and he was about to send for the family when he took sick, returned home and quickly died. Morris was only thirty-four years old. Abbie always thought he had been poisoned, possibly by his half-sister who felt she had a right to the property. An alternative theory is that he contracted Rocky Mountain spotted fever from a tick bite. One memento that Abbie kept of the connection to the Warm Springs Reservation was a juniper tree in the front yard of her Stevenson home. The tree still stands on that property. It was probably brought from Warm Springs as a seedling long ago, a dryland evergreen planted into one of the rainiest counties in Washington.

Morris’s passing didn’t make much material difference in the family’s way of life; they were scarcely poorer than they had always been. There was no welfare in those days and only occasional charity in a community where almost everyone lived on very little. Abbie wouldn’t have taken help anyway; she was too proud. She earned a little money by doing laundry for the mill crew. When her son Ray was old enough, he provided fish, deer and small game for the table. He was reputed to be adept at grabbing salmon out of the commercial fish wheels on the Columbia, quite a chancy undertaking. From time to time relatives would send boxes of cast-off clothes for the family to mend and wear. Although these pieces were old, the girls washed and ironed them to keep them fresh. Likely they had two sets of school clothes—one to wear and one to wash.

Abbie and her children survived, living in a shack in the woods just north of the town of Cascades (now North Bonneville) near Greenleaf Slough. Pans on the floor caught the rain where the roof leaked. Although they had not known who the owner was when they moved into the house, he turned out to be Mr. Porter of Portland whose family owned a well-known pasta factory. He occasionally came by the cabin as he went fishing, bringing them items from his business or sending other groceries up by train. Generally, they ate a lot of beans and the dozens of quarts of various wild berries they picked and canned throughout the summers. One afternoon the whole family—mother and five children—was in the woods gathering blackberries. Some white people came along and, delighted at seeing this “squaw” and her little brown brood wearing their Indian baskets and pails, inquired Tonto-style, “You catch ‘em berries?” to which Abbie replied in crisp, perfect English, “Yes, we’re picking berries.”

Abbie and her children survived, living in a shack in the woods just north of the town of Cascades (now North Bonneville) near Greenleaf Slough. Pans on the floor caught the rain where the roof leaked. Although they had not known who the owner was when they moved into the house, he turned out to be Mr. Porter of Portland whose family owned a well-known pasta factory. He occasionally came by the cabin as he went fishing, bringing them items from his business or sending other groceries up by train. Generally, they ate a lot of beans and the dozens of quarts of various wild berries they picked and canned throughout the summers. One afternoon the whole family—mother and five children—was in the woods gathering blackberries. Some white people came along and, delighted at seeing this “squaw” and her little brown brood wearing their Indian baskets and pails, inquired Tonto-style, “You catch ‘em berries?” to which Abbie replied in crisp, perfect English, “Yes, we’re picking berries.”

For a very long time, being Indian was not a good thing. Though raised in the white ways, it was impossible for Abbie and her children to escape their brown skin and racial discrimination. At school the other kids jeered “siwash” and laughed at their hand-me-down clothes and funny, old-fashioned shoes. Still, Abbie was a strong and self-sufficient woman determined to maintain her pride and self-respect. As an example, when it was near time for my mother, Kathleen, to be born Abbie took the scissors and string to bed with her every night—she could deliver that child herself; she didn’t want any white midwife fussing with her.

For a very long time, being Indian was not a good thing. Though raised in the white ways, it was impossible for Abbie and her children to escape their brown skin and racial discrimination. At school the other kids jeered “siwash” and laughed at their hand-me-down clothes and funny, old-fashioned shoes. Still, Abbie was a strong and self-sufficient woman determined to maintain her pride and self-respect. As an example, when it was near time for my mother, Kathleen, to be born Abbie took the scissors and string to bed with her every night—she could deliver that child herself; she didn’t want any white midwife fussing with her.

Abbie’s pride could make her seem tough and hard; she was never a “kindly old lady.” But that toughness was mostly a veneer to distance people she didn’t want to like, i.e., anyone not considered a relative carried a degree of mistrust for her. Specifically, that meant whites, whom she called by the Chinook jargon term “Bostons” (pronounced Bosh-tons with a slur in the middle that made it sound all the more derisive). She disliked her grandchildren playing with the white neighbor kids and tried to prevent it. When Abbie was older, a lady living up the street attempted to befriend her and get Abbie to teach her to crochet. When Abbie couldn’t stand it any longer, she told the lady to get out of the house and not come back again; she wanted her privacy.

Abbie didn’t really like her children’s white friends nor her daughters’ white husbands although she was always good and generous to them and their families. Yet that layer of toughness did sometimes present itself to her own children. None of Abbie’s three daughters merely grew up and left home; they were all kicked out because she was disgruntled with them for one reason or another. Probably at the base of it was maternal possessiveness or a kind of jealousy. As my mother and father went to get married in 1935 they stopped at Abbie’s house and asked her to go along to their ceremony, but Abbie refused. She knew she would cry at her daughter’s wedding and didn’t want anyone to see that.

Abbie didn’t really like her children’s white friends nor her daughters’ white husbands although she was always good and generous to them and their families. Yet that layer of toughness did sometimes present itself to her own children. None of Abbie’s three daughters merely grew up and left home; they were all kicked out because she was disgruntled with them for one reason or another. Probably at the base of it was maternal possessiveness or a kind of jealousy. As my mother and father went to get married in 1935 they stopped at Abbie’s house and asked her to go along to their ceremony, but Abbie refused. She knew she would cry at her daughter’s wedding and didn’t want anyone to see that.

Grandma Abbie in 1961 at grand daughter Sharleen’s wedding in Seattle.

This is not to say that Grandma Abbie was not giving. Although she was not at all religious, she bought a beautiful Bible from a door-to-door book salesman and gave it to my sister Juanita for her high school graduation. My first bank account was opened with pennies that Grandma Abbie saved for me in brown glass vitamin jars. Christmases brought dolls, miniature tea sets or other toys. While my mom was quite adept at sewing our clothes, I recall Grandma Abbie giving me two nice, store-bought dresses for my birthday when I was junior high age. Once Grandma Abbie and her second husband, Frank Estabrook, took one of my older sisters to the huckleberry fields with them. When they brought Sharleen back home Grandma Abbie told her to keep the berries she had picked. Sharleen said No, she’d picked them for Grandma. Abbie began to cry because a generous offer had been turned down. And she continued to cry until Sharleen agreed to keep the berries.

Abbie did not marry her second husband, Frank Estabrook, until her children were teenagers or older. Frank was half Indian, i.e., Native on his mother’s side and white on his father’s. We know little about his family but he was a man whom, my mother Kathleen said, she had always known as he lived in the area. Abbie’s and Frank’s marriage surprised the family, partly because Frank was twelve years older than Abbie so her daughters thought of him as an “old man.” However, Frank was a blacksmith and carpenter with a good job at Broughton Lumber Company sawmill in Willard, which provided company housing. During the hard times of the 1930s and World War II Frank always had work and so he and Abbie were comparatively prosperous.

While living mainly as the majority population did, Abbie and Frank were enrolled members of the Yakama Indian Tribe and attended tribal meetings in Toppenish each year which lasted several days. Some of the Native foods served at those meetings and other “Indian doings” in communities east of them like Rock Creek, Warm Springs and Toppenish were not to Grandma Abbie’s liking. While the salmon, elk and venison were fine, she had not been raised on the bland roots like camas and wapato that were served so she might bring her own food. That also let her know that it was properly prepared. In addition, she did not like the custom in some places of sitting on mats on the floor, perhaps because her bad hips made getting up and down difficult.

While living mainly as the majority population did, Abbie and Frank were enrolled members of the Yakama Indian Tribe and attended tribal meetings in Toppenish each year which lasted several days. Some of the Native foods served at those meetings and other “Indian doings” in communities east of them like Rock Creek, Warm Springs and Toppenish were not to Grandma Abbie’s liking. While the salmon, elk and venison were fine, she had not been raised on the bland roots like camas and wapato that were served so she might bring her own food. That also let her know that it was properly prepared. In addition, she did not like the custom in some places of sitting on mats on the floor, perhaps because her bad hips made getting up and down difficult.

Frank and Abbie carried on some traditionally Native activities like fishing in the Columbia for salmon, steelhead and sturgeon, all of which they canned or smoked for consumption throughout the year. Frank had built his own smokehouse in their backyard. They picked wild berries locally and on extended trips to the huckleberry fields near Mt. Adams where harvesting in a specified area is reserved for Indian people. For those trips they would take a big tent, woodstove and all the equipment to stay for up to two weeks and to can the berries right in the field. Various of their grandchildren accompanied them on these trips and recall the fun of it. Whenever we went to Grandma Abbie’s and Frank’s house for Sunday dinner, we could count on eating some kind of fish (“fish” was the word for all salmon and steelhead regardless of the sub-species) baked in the oven or sturgeon steaks fried atop the cast iron woodstove, “real” butter on our bread, and home-canned fruit or berries for dessert. No youngster went to their home without dipping into the covered candy jar kept for just such visitors and looking at, but not touching, the molded model horses standing on the living room window sill.

Abbie Estabrook & daughter Kathleen Reynolds, 1932

Abbie was born with a congenital hip defect that caused her to limp always and finally to use a cane or crutch. She was further crippled in her old age with arthritis and Frank suffered a broken hip which slowed down his very active life. Nevertheless, by the time Abbie was about seventy-five and Frank in his eighties she had become so exasperated with him that she began sleeping on the front porch of their home in Stevenson. When the winter snow started falling and blowing onto her bed, he finally gave in and enclosed the porch with walls. And there she slept, summer and winter, rain and snow until she was beyond caring for herself.

As Grandma Abbie became more ill, my mother and her sister Lucille went frequently to the house to care for her. They urged her to let them take her to the doctor but she refused, and they were trained not to cross her. When my oldest sister Juanita and her young family from Seattle stopped by, my brother-in-law took charge and called the ambulance. As the ambulance arrived, Grandma Abbie instructed, “You can have them back right up here by the front door.” Maybe she had to be stubborn with her daughters but knew the wisdom of the man’s direction.

As Grandma Abbie became more ill, my mother and her sister Lucille went frequently to the house to care for her. They urged her to let them take her to the doctor but she refused, and they were trained not to cross her. When my oldest sister Juanita and her young family from Seattle stopped by, my brother-in-law took charge and called the ambulance. As the ambulance arrived, Grandma Abbie instructed, “You can have them back right up here by the front door.” Maybe she had to be stubborn with her daughters but knew the wisdom of the man’s direction.

Grandma Abbie was unable to return home after that trip to the hospital, so went to a nursing home. Needless to say, she hated the facility. The people there thought they could make things more pleasant for her by putting her in a room with another elderly Indian woman—“They could talk to each other in Indian.” But it turned out that Grandma Abbie and that woman didn’t speak the same language as they were from separate areas along the Columbia River. Furthermore, Grandma Abbie didn’t think that lady very clean nor was she of the same Native social class, so Abbie didn’t want to associate with her. Neither did Grandma Abbie take to the other roommates – sweet little old lady types – she was given.

After about a year Frank joined her in the nursing home. They lived another two years, Abbie asking continually that they be allowed to go home, saying that Frank could take care of her and she could walk again if given a chance to build up her strength.

Grandma Abbie and Frank died just three months apart in 1968. She was 81 and he was 93 years old. They were laid to rest in the Cascade Indian & Pioneer Cemetery near North Bonneville, Washington, where each of their spouses and children who had preceded them in death was buried. That cemetery contains my parents, grandparents, great grandmother, and great-great grandmother plus aunts and uncles and cousins uncounted. It also features a mass grave for Indian remains removed from Bradford Island in the middle of the Columbia during the construction of nearby Bonneville Dam in the early 1930s. The monument for the group burial reads in Chinook jargon, “Ankutty tillikum musem” which translates, “[Here] the long-ago people sleep.” When we go to the cemetery on Memorial Day to carry on the 100-year plus tradition of decorating the family graves, we are always careful to avoid stepping directly on them. They are so old that, as my mother Kathleen taught us, they could sink in under our weight and we would be swallowed up.

Grandma Abbie and Frank died just three months apart in 1968. She was 81 and he was 93 years old. They were laid to rest in the Cascade Indian & Pioneer Cemetery near North Bonneville, Washington, where each of their spouses and children who had preceded them in death was buried. That cemetery contains my parents, grandparents, great grandmother, and great-great grandmother plus aunts and uncles and cousins uncounted. It also features a mass grave for Indian remains removed from Bradford Island in the middle of the Columbia during the construction of nearby Bonneville Dam in the early 1930s. The monument for the group burial reads in Chinook jargon, “Ankutty tillikum musem” which translates, “[Here] the long-ago people sleep.” When we go to the cemetery on Memorial Day to carry on the 100-year plus tradition of decorating the family graves, we are always careful to avoid stepping directly on them. They are so old that, as my mother Kathleen taught us, they could sink in under our weight and we would be swallowed up.

Before Grandma Abbie’s passing, she entrusted my mother with her collection of Klickitat-style baskets that were then displayed in our home. One of the baskets had been purchased by Abbie from an old Indian woman for my mother Kathleen when she was five years old. It is one of those unadorned but beautiful tightly woven spruce root and cedar bark baskets with the loops on the top that you wear tied around your waist when you pick berries, which we did. Those baskets as well as the stories I relate here helped me grow up feeling surrounded by my Indian heritage. Our family has donated the basket collection to the Skamania County Interpretive Center so it can be enjoyed by all of Abbie’s descendants and the community at large.

Before Grandma Abbie’s passing, she entrusted my mother with her collection of Klickitat-style baskets that were then displayed in our home. One of the baskets had been purchased by Abbie from an old Indian woman for my mother Kathleen when she was five years old. It is one of those unadorned but beautiful tightly woven spruce root and cedar bark baskets with the loops on the top that you wear tied around your waist when you pick berries, which we did. Those baskets as well as the stories I relate here helped me grow up feeling surrounded by my Indian heritage. Our family has donated the basket collection to the Skamania County Interpretive Center so it can be enjoyed by all of Abbie’s descendants and the community at large.

For her grandchildren and great grandchildren, part of the legacy from our Grandma Abbie is the Native heritage which has allowed us membership in the Yakama or Cowlitz Tribes. The Cascade tribe of Mary Stooquin was subsumed under the Yakama tribal umbrella and so Abbie and her children enrolled there. Soon after my three older siblings (Juanita, Robert and Sharleen) were born, the family moved to Goldendale which was in the original Yakama territory, so those three children were able to enroll at Yakama. Their cousins who lived near Stevenson were outside that territory so could not enroll at Yakama. When I and my twin sisters (Leslie and Linda) were born, the Yakama Tribe did not extend enrollment to us, either. However, in the early 1970s the Cowlitz Tribe entered into the federal acknowledgement process and we realized that our connection to Louis Gerand would allow us to enroll with the Cowlitz. We did so and many of us and our cousins who are also descended from Abbie became and remain active in the Cowlitz Tribe, including in leadership roles. When we joined the Cowlitz we discovered a whole new world of cousins from that side of the family that had been unknown to us due to Louis Gerand’s absence from most of Grandma Abbie’s life. This may sound convoluted, but Indians have complicated family stories like that—it just comes with the territory.

Abbie’s daughters: Mary Miller, Kathleen Williams, Lucille Aalvik at the Tumulth reunion, circa 1976

[This paper was originally written in 1972 as a college assignment by Marsha Williams, daughter of Kathleen Williams, who was the youngest daughter of Abbie Weiser/Reynolds/Estabrook. It was revised in 2018 with input from all of Kathleen’s children, her sister Lucille Aalvik’s surviving children and her sister Mary Miller’s grandchildren. I am grateful for everyone’s memories and assistance.]

Copyright © Marsha J. Williams, 2018. Reproduction or distribution to the public requires express written permission of the author

First, she pulled out a wonderful medicine blanket that she made for as a gift. It was very long, and when she unfurled it, the length of it tumbled over the cliff for many yards. As she began to gather it back up into a neat roll, she smiled lovingly. She had spent many moons making this blanket, and each stitch contained a prayer. This blanket had very powerful protective medicine. She placed the rolled-up medicine blanket into the saddlebag on the Eagle. Then she handed me a magic compass. The compass was made entirely of quartz crystal. She showed me precisely how to use it for navigation. The face of the compass was completely blank, empty of all markings. It had a clear crystal face, with a quartz crystal needle. The compass would guide us on our journey. Finally, she handed me a key, carved out of jade. I placed the key in my medicine pouch. Crow Dancer danced around and flapped his wings and stomped his feet and made a blessing for the journey, and we were off again.

First, she pulled out a wonderful medicine blanket that she made for as a gift. It was very long, and when she unfurled it, the length of it tumbled over the cliff for many yards. As she began to gather it back up into a neat roll, she smiled lovingly. She had spent many moons making this blanket, and each stitch contained a prayer. This blanket had very powerful protective medicine. She placed the rolled-up medicine blanket into the saddlebag on the Eagle. Then she handed me a magic compass. The compass was made entirely of quartz crystal. She showed me precisely how to use it for navigation. The face of the compass was completely blank, empty of all markings. It had a clear crystal face, with a quartz crystal needle. The compass would guide us on our journey. Finally, she handed me a key, carved out of jade. I placed the key in my medicine pouch. Crow Dancer danced around and flapped his wings and stomped his feet and made a blessing for the journey, and we were off again.

We have become fast friends and I have learned a great deal from his wisdom. We have started working together on story gathering projects here at

We have become fast friends and I have learned a great deal from his wisdom. We have started working together on story gathering projects here at

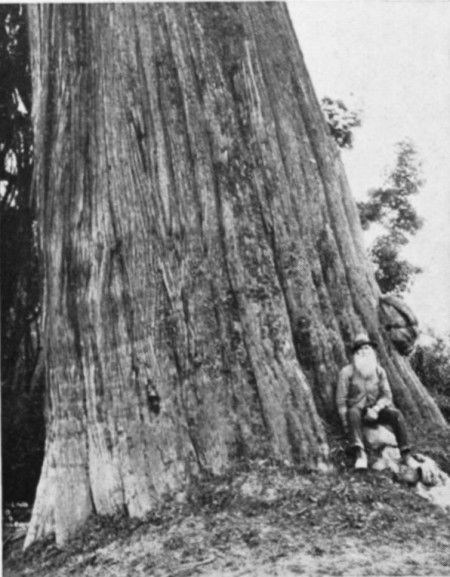

(I consider myself a local but I need to live around here for 10 years, to become an “official local”, I am told.) about this elusive fairy land that had captured my imagination. Some people were reluctant to speak of it’s whereabouts, as if holding on to an old code of silence, looking me over with suspicious eyes. I would ‘prime the pump’ with cheap beer to get the lips telling stories, and got little clues. Most would boast about taking their girlfriend out there and writing their names on the holy grail of the ‘Stump”.

(I consider myself a local but I need to live around here for 10 years, to become an “official local”, I am told.) about this elusive fairy land that had captured my imagination. Some people were reluctant to speak of it’s whereabouts, as if holding on to an old code of silence, looking me over with suspicious eyes. I would ‘prime the pump’ with cheap beer to get the lips telling stories, and got little clues. Most would boast about taking their girlfriend out there and writing their names on the holy grail of the ‘Stump”.