The constant sounds of falling water and rustling winds make up much of the landscape of the Gorge.

Dog Creek Falls, Washington

The constant sounds of falling water and rustling winds make up much of the landscape of the Gorge.

Dog Creek Falls, Washington

Myself, I’m one of the generations. My mother is one of the generations, wandering out there in alcoholism, and death, and murder, and domestic violence, and thinking there’s no way out. Well, there is a way out… Like I tell my children, my grandchildren, ‘You don’t have to walk that road of alcoholism and drug addiction. I walked that road. I took all those beatings for you guys. You don’t have to walk that road.’

- Verna Bartlett, Ph.D., Native American elder and sexual abuse survivor

My sweet Grandmother and myself in 2009.

I recorded this from my Grandmother while she was waiting to go home for Hospice and pass on to her Creator.

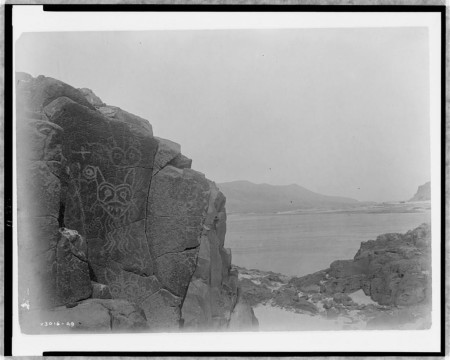

Across many North American indigenous cultures, the thunderbird carries many of the same characteristics. It is described as a large bird, capable of creating storms and thundering while it flies. Clouds are pulled together by its wingbeats, the sound of thunder made by its wings clapping, sheet lightning the light flashing from its eyes when it blinks, and individual lightning bolts made by the glowing snakes that it carries around with it. In masks, it is depicted as multi-colored, with two curling horns, and, often, teeth within its beak.

This Thunderbird petroglyph rests at Horsetheif Lake in the east end of the Columbia River Gorge, in Washington.

The salt of time has worn the edges a little thin as the image wains in it’s slow compost. The timeless ghost of the unidentified figure suspended in haunted air. This bridge between the past and now, triggers my own memories, sneaking across forbidden entries, to break to the other side, and bathe in the glory of the Springs. The constant murmur of white waters washing across old stones and the sulphured air, and many generations baptized. I have come to believe that this is where the Gods live.

Two swinging bridges across Wind River. An unidentified person stands on one bridge. Written on the back of photo- “Swinging bridge Shipherd’s Hot Springs.”

“No one must look at the rocks of the bridge. People knew that some day it would fall. They must not anger the Spirit Chief by looking at it, their wise men told them.

‘Bridge of the Gods’ ca. 1929, photographer unknown.

Read more here

I woke up a bit before the Morning Star and could hear the silence of subfuscus mists hovering upon the hills and valleys. I laid awake, and reminisced about early mornings at Oceti Sakowin Camp in 2016, “Wake up, this is not a vacation!”.. I awaken to broken silence, echoing off old canyons, where trees fold time in the roots of soggy soil, I ponder my dreams.

Taowhywee, Morning Star

My partner awakes to make some coffee and prepare herself for the journey. She knew Grandma Aggie personally, and looked up to her as a fellow Grandmother herself, learning to walk into Elder-hood. I watch her braid her hair with stories of Grandma, and what she meant to her. About her regrets of not staying in touch more, but holding the sacred memory close, she releases a single tear. I prepare the car for our journey to the Siletz Reservation, where we will lay Grandmother’s bones along side her relatives. As I am walking to the car, I hear my own Grandmothers voice in my head, and look up to greet the horizon. The young morning star obscured in fog seems so enchanted and calm. A deep breath overtakes me as I greet the day. I pray, remembering.

{Listen to my Grandmother, Shirley Amos, talking about finding our place in the sun.}

Our drive meanders through the Oregon Coast Range. The mists ebb and flow like the Ocean waves crashing against the shores of broken trees.

Hwy 20 west to Siletz Reservation. © H a v e n

Just as our stories are heartbreaking and traumatic, they are also laced in resilience and joy. There is a deep belonging to Place that fuels an inner fire no colonial power can kill, and no god can enslave. Yet, the scars are deep and seeping, and our Mother is in danger. We must find our place in the Sun, and rise above for the future generations. Thank you Grandma Aggie for the reminders, and the Stories.

The smells mingled in a frenzy of excitement, swaying with the brisk winds, carrying laughter and conversations into the chilly August night.

1954 Skamania County Fair: unknown photographer.

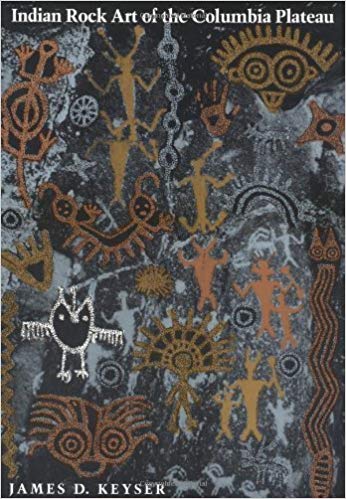

Written by: James D. Keyser, Indian rock art of the Columbia Plateau

Rock art is one of the most common types of archaeological site in Oregon, occurring from the Portland Basin to Hell’s Canyon and the high desert canyons along the Owyhee River to far southwestern Oregon’s Rogue River drainage. Including both pictographs (paintings) and petroglyphs (carvings), the rock art at these sites was created as early as 7,000 years ago until as recently as the late 1800s. Although petroforms—a third type of rock art composed of outlines cut in desert pavement or boulders laid out in the form of animals or humans—are found elsewhere in North America, none has been discovered in Oregon.

Including both pictographs (paintings) and petroglyphs (carvings), the rock art at these sites was created as early as 7,000 years ago until as recently as the late 1800s. Although petroforms—a third type of rock art composed of outlines cut in desert pavement or boulders laid out in the form of animals or humans—are found elsewhere in North America, none has been discovered in Oregon.

Archaeologists have classified Oregon’s rock art into five traditions, that is, spatially broad-based artistic expressions that were created during a defined period of time. The traditions generally follow Oregon’s aboriginal ethnic/cultural boundaries. Thus, the Columbia Plateau Tradition reflects the art of Sahaptian-speaking tribes such as the Tenino, Nez Perce, Umatilla, and Klamath-Modoc, while the Great Basin Tradition comprises the art of the Numic-speaking bands of the Northern Paiute. In the river valleys of western Oregon, the few sites that are known represent the Columbia Plateau Tradition and a little-known California rock art expression called the Far Western Pit and Groove Tradition, which is the product of Tututni and Kalapuya artists and probably members of other tribes as well.

Cover to book text is from.

The subject matter of rock art in the Columbia Plateau Tradition is primarily humans, animals, and geometric designs, one of the most common of which is tally marks—a horizontally oriented series of three to more than thirty short, vertical, evenly spaced, finger-painted lines. Despite its limited subject matter, Columbia Plateau art functioned in several ways, including as a commemoration of the acquisition of spirit power during a vision quest and as a shaman’s ritual expression of power.

Yakima Polychrome designs and the closely related imagery of the Columbia River Conventionalized Style of the Northwest Coast Tradition served in healing and mortuary rituals and were used to witness mythic beings and places. Some images of animals and hunters in the Columbia Plateau Tradition were painted and carved as hunting magic. In the Klamath Basin, art in the Columbia Plateau Tradition has several stylistic expressions, but current research suggests that all of them were the exclusive purview of shamans.

Columbia River Gorge

Far Western Pit and Groove Tradition rock art is found from the southern Willamette Valley near Eugene into the Umpqua and Rogue River drainages, where it occurs as cupules—shallow dimples—and simple geometric forms pecked and ground into streamside boulders. Known as Baby Rocks or Rain Rocks, ethnographic sources indicate that these simple petroglyphs were carved both by shamans accessing and using supernatural power to call the salmon and communicate with the gods and by women who wanted to bear a child.

Vantage, WA.

Certainly much Great Basin rock art was made by shamans who were acquiring or using supernatural power, and much of the geometric imagery may have been generated in the artists’ minds by stimuli experienced during a trance. Other Great Basin imagery, however, is likely to have been made in conjunction with subsistence activities during the seasonal round of these high-desert hunter-gatherers and likely had a broader function as part of the rituals associated with subsistence.

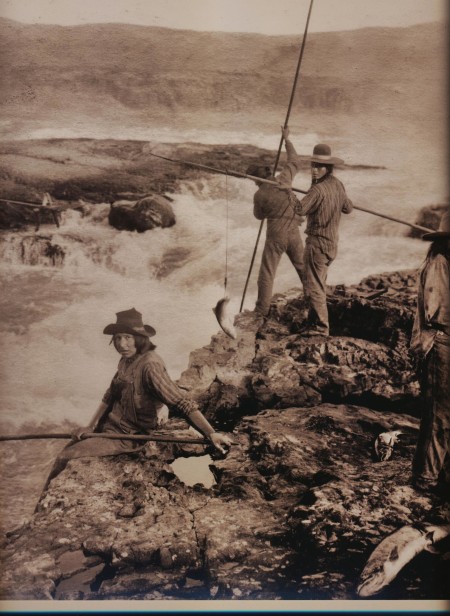

This photo really sums up in an image what this project is about to me. I can imagine what it would feel like to be Great Grandmother, watching the old ways die underneath the feet of something new. The very landscape has been rearranged and so has our Story. This photo is of the Cascades and Cascade Locks, Oregon prior to bonneville dams construction in the early 30′s.

A photo taken just before the Cascades were silenced. 193?, photo author unknown.

Read more about Bonneville Dam’s impact on my ancestors here

Celilo – Wyam 2005 Salmon Feast

Loss of Wyam caused pervasive sadness, even in celebratory events. The old Longhouse is gone. The Wyam, or Celilo Falls, are gone. Still courage, wisdom, strength and belief bring us together each season to speak to all directions the ancient words. There is no physical Celilo, but we have our mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, and our children bound together for all possible life in the future. We are salmon (Waykanash). We are deer (Winat). We are roots (Xnit). We are berries (Tmanit). We are water (Chuush). We are the animation of the Creator’s wisdom in Worship song (Waashat Walptaikash).

Unknown fishermen, unknown year, unknown photographer.. any information would be appreciated.

The leader speaks in the ancient language’s manner. He speaks to all in Ichiskiin. He says, “We are following our ancestors. We respect the same Creator and the same religion, each in turn of their generation, and conduct the same service and dance to honor our relatives, the roots, and the salmon. The Creator at the beginning of time gave us instruction and the wisdom to live the best life. The Creator made man and woman with independent minds. We must choose to live by the law, as all the others, salmon, trees, water, air, all live by it. We must use all the power of our minds and hearts to bring the salmon back. Our earth needs our commitment. That is our teachings. We are each powerful and necessary.”

published in River of Memory: The Everlasting Columbia,Layman,WilliamD.,Ed. UP: WA. Seattle, WA 2006