Chinook – Many Swans: Sun Myth of the North American Indians

Lowell, Amy (1920)

[NOTE. -- "Many Swans" is based upon a Kathlamet legend, the main theme and many of the episodes of which I have retained, while at the same time augmenting and freely departing from it in order to gain a wider symbolism. Four of the songs in my poem are real Indian songs, one is an adaptation, the others are merely in the Indian idiom. In the interest of atmospheric truth, I have felt at liberty to make occasional use of Indian expressions and turns of thought, and I here wish to record my gratitude to that small body of indefatigable workers in that field of Indian folk-lore and tradition whose careful and exact translations of Indian texts have made them accessible to those who, like myself, have not the Indian tongues. -- A. L.]

When the Goose Moon rose and walked upon a pale sky, and water made a noise once more beneath the ice on the river, his heart was sick with longing for the great good of the sun. One Winter again had passed, one Winter like the last. A long sea with waves biting each other under grey clouds, a shroud of snow from ocean to forest, snow mumbling stories of bones and driftwood beyond his red fire. He desired space, light; he cried to himself about himself, he made songs of sorrow and wept in the corner of his house. He gave his children toys to keep them away from him. His eyes were dim following the thin sun. He said to his wife: “I want that sun. Some day I shall go to see it.” And she said: “Peace, be still. You will wake the children.”

So he waited, and the Whirlwind Moon came, a crescent — mounted, and marched down beyond the morning, and was gone. Then the Extreme Cold Moon came and shone, it mounted, moved night by night into morning and faded through day to darkness. He watched the Old Moon pass, he saw the Eagle Moon come and go. Slowly the moons wound across the snow, and many nights he could not see them, he could only hear the waves raving foam and fury until dawn.

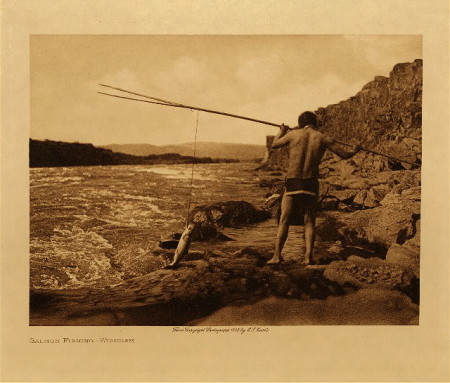

Now the Goose Moon told him things, but his blood lay sluggish within him until the moon stood full and apart in the sky. His wife asked why he was silent. “I have wept my eyes dry,” he answered. “Give me my cedar bow and my two-winged arrows with the copper points. I will go into the forest and kill a moose, and bring fresh meat for the children.”

All day he stalked the forest. He saw the marks of bears’ claws on the trees. He saw the wide tracks of a lynx, and the little slot-slot-of a jumping rabbit, but nothing came along. Then he made a melancholy song for himself: “My name is Many Swans, but I have seen neither sparrow nor rabbit, neither duck nor crane. I will go home and sit by the fire like a woman and spin cedar bark for fish-lines.”

Then silver rain ran upon him through the branches from the moon, and he stepped upon open grass and laughed at the touch of it under his foot.” I will shoot the moon,” he thought, “and cut it into cakes for the children.”

He laid an arrow on his bow and shot, and the copper tip made it shine like a star flying. He watched to see it fall, but it did not. He shot again, and his arrow was a bright star until he lost it in the brilliance of the moon. Soon he had shot all his arrows, and he stood gaping up at the moonshine wishing he had not lost them.

Then Many Swans laughed again because his feet touched grass, not snow. And he gathered twigs and stuck them in his hair, and saw his shadow like a tree walking there. But something tapped the twigs, he stood tangled in something. With his hand he felt it, it was the feather head of an arrow. It dangled from the sky, and the copper tip jangled upon wood and twinkled brightly. This — that — and other twinkles, pricking against the soft flow of the moon, and the wind crooned in the arrow-feathers and tinkled the bushes in his hair.

Many Swans laid his hand on the arrow and began to climb — up — up — a long time. The earth lay beneath him wide and blue, he climbed through white moonlight and purple air until he fell asleep from weariness.

Sunlight struck sidewise on a chain of arrows, below were cold clouds above a sky blooming like an open flower and he aiming to the heart of it. Many Swans saw that up was far, and down was also far, but he cried to himself that he had begun his journey to the sun. Then he pulled a bush from his hair, and the twigs had leaved and fruited, and there were salmon-berries dancing beneath the leaves. “My father, the sun, is good,” said Many Swans, and he eat the berries and went on climbing the arrows into the heart of the sky.

He climbed till the sun set and the moon rose, and at midmost moon he fell asleep to the sweeping of the arrow-ladder like a cradle in the wind.

When dawn struck gold across the ladder, he awoke. “It is Summer,” said Many Swans, “I cannot go back, it must be more days down than I have travelled. I should be ashamed to see my children, for I have no meat for them. “Then he remembered the bushes, and pulled another from his hair, and there were blue huckleberries shining like polished wood in the midst of leaves. “The sun weaves the seasons,” thought Many Swans, “I have been under and over the warp of the world, now I am above the world,” and he went on climbing into the white heart of the sky.

Another night and day he climbed, and he eat red huckleberries from his last bush, and went on — up and up — his feet scratching on the ladder with a great noise because of the hush all round him. When he reached an edge he stepped over it carefully, for edges are thin and he did not wish to fall. He found a tall pine-tree by a pond. “Beyond can wait,” reasoned Many Swans, “this is surely a far country.” And he lay down to sleep under the pine-tree, and it was the fourth sleep he had had since he went hunting moose to bring meat to his family.

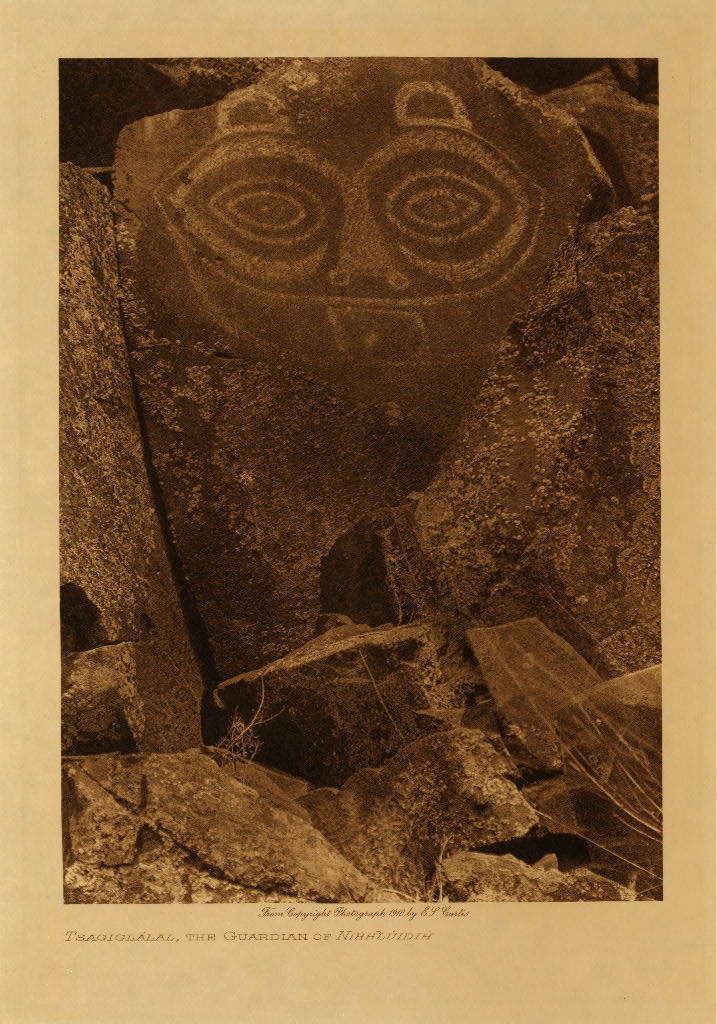

The shadow crept away from him, and the sun came and sat upon his eyelids, so that by and by he opened them and rubbed his eyes because a woman stared at him, and she was beautiful as a salmon leaping in Spring. Her skirt was woven of red and white cedar bark, she had carved silver bracelets and copper bracelets set with haliotis shell, and earrings of sharks’ teeth. She sparkled like a river salmon, and her smile was water tipping to a light South breeze. She pleased the heart of Many Swans so that fear was not in him, only longing to take her for himself as a man does a woman, and he asked her name. “Grass-Bush-and-Blossom is my name,” she answered, “I am come after you. My grandmother has sent me to bring you to her house.” “And who is your grand-mother?” asked Many Swans. But the girl shook her head, and took a pinch of earth from the ground and threw it toward the sun. “She has many names. The grass knows her, and the trees, and the fishes in the sea. I call her ‘grandmother,’ but they speak of her as ‘The-One-Who-Walks-All-Over-the-Sky.’” Many Swans marvelled and said nothing, for things are different in a far country.

They walked together, and the man hungered for the woman and could not wait. But he said no word, and he eat up her beauty as though it were a ripe foam-berry and still went fasting until his knees trembled, and his heart was like hot dust, and his hands ached to thrust upon her and turn her toward him. So they went, and Many Swans forgot his wife and children and the earth hanging below the sharp edge of the sky.

* * *

The South wind sat on a rock and never ceased to blow, locking the branches of the trees together; a flock of swans rose out of the South-East, one and seven, making strange, changing lines across a smooth sky. Wild flax-blossoms ran blue over the bases of black and red totem poles. The colours were strong as blood and death, they rattled like painted drums against the eyesight. “Many Swans!” said the girl and smiled. “Blood and death,” drummed the totem poles. “Alas!” nodded the flax. The man heeded nothing but the woman and the soles of his feet beating on new ground.

The houses were carved with the figures of the Spring Salmon. They were carved in the form of a rainbow. Hooked noses stood out above doorways; crooked wooden men crouched, frog-shaped, gazing under low eaves. It was a beautiful town, ringing with colours, singing brightly, terribly, in the smooth light. All the way was sombre and gay, and the man walked and said nothing.

They came to a house painted black and carved with stars. In the centre was a round moon with a door in it. So they entered and sat beside the fire, and the woman gave the man fish-roes and gooseberries, but his desire burnt him and he could not eat.

Grass-Bush-and-Blossom saw his trouble, and she led him to a corner and showed him many things. There were willow arrows and quivers for them. There were mountain-goat blankets and painted blankets of two elkskins, there were buffalo skins, and dressed buckskins, and deerskins with young, soft hair. But Many Swans cared for nothing but the swing of the woman’s bark skirt, and the sting of her loveliness which gave him no peace.

Grass-Bush-and-Blossom led him to another corner, and showed him crest helmets, and wooden armour; she showed him coppers like red rhododendron blooms, and plumes of eagles’ wings. She gave him clubs of whalebone to handle, and cedar trumpets which blow a sound cool and sweet as the noise of bees. But Many Swans found no ease in looking save at her arms between the bracelets, and his trouble grew and pressed upon him until he felt strangled.

She led him farther and showed him a canoe painted silver and vermilion with white figures of fish upon it, and the gunwales fore and aft were set with the teeth of the sea-otter. She lifted out the paddles, the blades were shaped like hearts and striped with fire-hues. She said, “Choose. These are mine and my grand-mother’s. Take what you will.” But Many Swans was filled with the glory of her standing as a young tree about to blossom, and he took her and felt her sway and: fold about him with the tightness of new leaves. “This” — said Many Swans, “this — for am I not a man!” So they abode and the day ran gently past them, slipping as river water, and evening came, and someone entered, darkening the door.

Then Grass-Bush-and-Blossom wrapped her cedar-bark skirt about her and sprang up, and her silver and copper ornaments rang sweetly with her moving. The-One-Who-Walks-All-Over-the-Sky looked at Many Swans. “You have not waited,” she said. “Alas! It is an evil beginning. My son, my son, I wished to love you.” But he was glad and thought: “It is a querulous old woman, I shall heed her no more than the snapping of a fire of dead twigs.”

The old woman went behind the door and hung up something. It pleased him. It was shining. When he woke in the night, he saw it in the glow of the fire. He liked it, and he liked the skins he lay on and the woman who lay with him. He thought only of these things.

In the morning, the old woman unhooked the shining object and went out, and he turned about to his wife and said sharp, glad words to her and she to him, and the sun shone into the house until evening, and in the night again he was happy, because of the thing that glittered and flashed and moved to and fro, clashing softly on the wall.

The days were many. He did not count them. Every morning the old woman took out the shining thing, and every evening she brought it home, and all night it shone and cried “Ching-a-ling” as it dangled against the wall.

Moons and moons went by, no doubt. Many Swans did not reckon them out. Was there an earth? Was there a sky? He remembered nothing. He did not try. And then one day, wandering along the street of carved houses, he heard a song. He heard the beat of rattles and drums, and the shrill humming of trumpets blown to a broken rhythm:

“Haioo’a! Haioo!

Many salmon are coming ashore,

They are coming ashore to you, the post of our heaven,

They are dancing from the salmon’s country to the shore.

I come to dance before you at the right-hand side of the world, overtowering, outshining, surpassing all. I, the Salmon!

Haioo’a! Haioo!”

And the drums rumbled like the first thunder of a year, and the rattles pattered like rain on flower petals, and the trumpets hummed as wind hums in round-leafed trees; and people ran, jumping, out of the Spring Salmon house and leapt to the edge of the sky and disappeared, falling quickly, calling the song to one another as they fell so that the sound of it continued rising up for a long time.

Many Swans listened, and he recollected that when the Spring Salmon jump, the children say: “Ayuu! Do it again!” He thought of his children and his wife whom he had left on the earth, and wondered who had brought them meat, who had caught fish for them, and he was sad at his thoughts and wept, saying: “I want to shoot birds for my children. I want to spear trout for my children.” So he went back to his house, and his feet dragged behind him like nets drawn across sand.

He lay down upon his bed and grieved, because he had no children in the sky, and because the wife of his youth was lost to him. He would not eat, but lay with his head covered and made no sound.

Then Grass-Bush-and-Blossom asked him: “Why do you grieve?” But he was silent. And again she said: “Why do you grieve?” But he answered nothing. And she asked him many times, until at last he told her of his children, of his other wife whom he had left, and she was pitiful because she loved him.

When the old woman came, she also said: “What ails your husband that he lies there saying nothing?” And Grass-Bush-and-Blossom answered: “He is homesick. We must let him depart.”

Many Swans heard what she said, and he got up and made himself ready. Now the old woman looked sadly at him. “My son,” she said, “I told you it was a bad beginning. But I wish to love you. Choose among these things what you will have and return to your people.”

Many Swans pointed to the shining thing behind the door and said, “I will have that.” But the old woman would not give it to him. She offered him spears of bone, and yew bows, and arrows winged with ducks’ feathers. But he would not have them. She offered him strings of blue and white shells, and a copper canoe with a stern-board of copper and a copper bailer. He would not take them. He wanted the thing that glittered and cried “Ching-a-ling” as it dangled against the wall. She offered him all that was in the house. But he liked that great thing that was shining there. When that thing turned round it was shining so that one had to close one’s eyes. He said: “That only will I have.” Then she gave it to him saying: “You wanted it. I wished to love you, and I do love you.” She hung it on him. “Now go home.”

Many Swans ran swiftly, he ran to the edge of the sky, there he found the land of the rainbow. He put his foot on it and went down, and he felt strong and able to do anything. He forgot the sky and thought only of the earth.

Many Swans made a song as he went down the rainbow ladder. He sang with a loud voice:

“I will go and tear to pieces Mount Stevens, I will use it for stones for my fire.

I will go and break Mount Qa-tsta-is, I will use it for stones for my fire.

All day and all night he went down, and he was so strong he did not need to sleep. The next day he made a new song. He shouted it with a great noise:

“I am going all round the world,

I am at the centre of the world,

I am the post of the world,

On account of what I am carrying in my hand.”

This pleased him, and he sang it all day and was not tired at all.

Four nights and days he was going down the ladder, and every day he made a song, and the last was the best. This was it!

“Oh wonder! He is making a turmoil on the earth.

Oh wonder! He makes the noise of falling objects on the earth.

Oh wonder! He makes the noise of breaking objects on the earth.”

He did not mean this at all, but it was a good song. That is the way with people who think themselves clever. Many Swans sang this song a great many times, and on the fourth day, when the dawn was red, he touched the earth and walked off upon it.

* * *

When Many Swans arrived on the earth, he was not very near his village. He stood beneath a sea-cliff, and the rocks of the cliff were sprinkled with scarlet moss as it might have been a fall of red snow, and lilac moss shouldered between boulders of pink granite. Far out, the sea sparkled all colours like an abalone shell, and red fish sprang from it — one and another, over its surface. As he gazed, a shadow slipped upon the water, and, looking up, he saw a raven flying and overturning as it flew. Red fish, black raven — blood and death — but Many Swans called “Haioho-ho!” and danced a long time on the sea-sand because he felt happy in his heart.

He heard a robin singing, and as it sang he walked along the shore and counted his fingers for the headlands he must pass to reach home. He saw the canoes come out to fish, he said the names of his friends who should be in them. He thought of his house and the hearth strewn with white shells and sand. When the canoes of twelve rowers passed, he tried to signal them, but they went by too far from land. The way seemed short, for all day he told himself stories of what people would say to him. “I shall be famous, my fame will reach to the ends of the world. People will try to imitate me. Every one will desire to possess my power.” So Many Swans said foolish things to himself, and the day seemed short until the evening when he came in sight of his village.

At the dusky time of night, he came to it, and he heard singing, so he knew his people were having a festival. He could hear the dance-sticks clattering on the cedar boards and the moon-rattles whirling, and he could see the smoke curling out of the smoke-holes. Then he shouted very much and ran fast, but as he ran, the thing which he carried in his hands shook and cried: “We shall strike your town.” Then Many Swans went mad; he turned, swirling like a great cloud, he rose as a pillar of smoke and bent in the wind as smoke bends, he streamed as bands of black smoke, and out of him darted flames, red-mouthed flames, so that they scorched his hair. His hands were full of blood, and he yelled “Break! Break! Break! Break!” and did not know whose voice it was shouting.

There was a tree, and a branch standing out from it, and fire came down and hung on the end of the branch. He thought it was copper which swung on the tree, because it twirled and had a hard edge. Then it split as though a wedge had riven it, and burst into purple flame. The tree was consumed, and the fire leapt laughing upon the houses and poured down through the roofs upon the people. The flame-mouths stuck themselves to the houses and sucked the life from all the people, the flames swallowed themselves and brought forth little flames which ran a thousand ways like young serpents just out of their eggs, till the fire girdled the village and the water in front curdled and burned like oil.

Then Many Swans knew what he had done, and he tried to throw away his power which was killing everybody. But he could not do it. The people lay there dead, and his wife and children among the dead people. His heart was sick, and he cried: “The weapon flew into my hands with which I am murdering,” and he tried to throw it away, but it stuck to his flesh. He tried to cut it apart with his knife, but the blade turned and blunted. He cried bitterly: “Ka! Ka! Ka! Ka!” and tried to break what he wore on a stone, but it did not break. Then he cut off his hair and blackened his face, and turned inland to the spaces of the forest, for his heart was dead with his people. And the moon followed him over the tops of the trees, but he hated the moon because it reminded him of the sky.

* * *

A long time Many Swans wandered in the forest. White-headed eagles flew over the trees and called down to him: “There is the man who killed everybody.” By night the owls hooted to each other: “The man who sleeps has blood on him, his mouth is full of blood, he let loose his power on his own people.” Many Swans beat upon his breast and pleaded with the owls: “You with ears far apart who hear everything, you the owls, it was not I who killed but this evil thing I carry and which I cannot put down.” But the owls laughed, shrill, mournful, broken laughs, repeating the words they had said, so that Many Swans could not sleep and in the morning he was so weak he shook when he walked.

He walked among pines which flowed before him in straight, opening lines like water, and the wind in the pine-branches wearied his soul as he heard it all day long. At first he eat nothing, but when he stumbled and fell for faintness he gathered currants and partridge-berries and so made his feet carry him on.

He came to a wood of red firs where fire had been before him. The heartwood of the firs was all burnt out, but the trees stood on stilts of sapwood and mocked the man who slew with fire.

He passed through woods of spear-leaf trees, with sharp vines head-high all about them. He thrust the thing he carried into the vines and tried to let go of it, but it would not stay tangled and came away in his hand.

He heard beavers drumming with their tails on water, and saw musk-rats building burrows with the stalks of wild rice in shoal water but they scattered as he came near. The little animals fled before him in fear, chattering to each other. Even the bears deserted the huckleberry bushes when they heard the fall of his foot, so that he walked alone. Above him, the waxwings were catching flies in the spruce-tops, they were happy because it was Summer and warm, they were the only creatures too busy to look down at the man who moved on as one who never stops, making his feet go always because there was nothing else to do.

By and by the trees thinned, and Many Swans saw beyond them to a country of tall grass. He rested here some time eating fox-grapes and blackberries, for indeed he was almost famished, and weary with the sickness of solitude. He thought of the ways of men, and hungered after speech and comforting. But he saw no man, and the prairie frightened him, rolling endlessly to the sky.

At last his blood quickened again, and the longing for people beat a hard pulse in his throat so that he rose and went on, seeking where he might find men. For days he sought, following the trails of wild horses and buffalo, tripping among the crawling pea-vines, bruised and baffled, blind with the sharp shimmer of the grass.

Then suddenly they came, riding out of the distance on both sides of him. These men wore eagle-plume bonnets, and their horses went so fast he could not see their legs. They ran glittering toward one another, whooping and screaming, and the horses’ tails streamed out behind them stiffly like bunches of bones. Each man lay prone on his horse and shot arrows, hawk-feathered arrows, owl-feathered arrows, and they were terrible in swiftness because the feathers had not been cut or burned to make them low.

The arrows flew across one another like a swarm of grasshoppers leaping, and the men foamed forward as waves foam at a double tide.

They came near, bright men, fine as whips, striding lithe cat horses. One rode a spotted horse, and on his head was an upright plume of the tail-feathers of the black eagle. One rode a buckskin horse, long-winded and chary as a panther. One rode a sorrel horse painted with zigzag lightnings. One rode a clay-coloured horse, and the figure of a kingfisher was stamped in blue on its shoulder. Wildcat running horses, and their hoofs rang like thunder-drums on the ground, and the men yelled with brass voices:

“We who live are coming.

Ai-ya-ya-yai!

We are coming to kill.

Ai-ya-ya-yai!

We are coming with the snake arrows,

We are coming with the tomahawks

Which swallow their faces.

Ai-ya-ya-yai!

We will hack our enemies.

Ai-ya-ya-yai!

We will take many scalps.

Ai-ya-ya-yai!

We will kill — kill — kill — till every one is dead.

Ai-ya-ya-ya-yai!”

Many Swans lay in a buffalo wallow and hid, and a white fog slid down from the North and covered the prairie. For a little time he heard the war-whoops and the pit-pit of hitting arrows, and then he heard nothing, and he lay beneath the cold fog hurting his ears with listening. When the sky was red in the evening and the fog was lifted, he shifted himself and looked above the grass. “Alas!” Alas!” wept Many Swans, “the teeth of their arrows were like dogs’ teeth. They have devoured their enemies.” For nobody was there, but the arrows were sticking up straight in the ground. Then Many Swans went a long way round that place for he thought that the stomachs of the arrows must be full of blood. And so he went on alone over the prairie, and his heart was black with what he had seen.

* * *

A stream flowed in a sunwise turn across the prairie, and the name of the stream was “Burnt Water,” because it tasted dark like smoke. The prairie ran out tongues of raw colors — blue of camass, red of geranium, yellow of parsley — at the young green grass. The prairie flung up its larks on a string of sunshine, it lay like a catching-sheet beneath the black breasts balancing down on a wind, calling “See it! See it! See it!” in little round voices.

Antelope and buffalo,

Threading the tall green grass they go,

To and fro, to and fro.

And painted Indians ride in a row,

With arrow and bow, arrow and bow,

Hunting the antelope, the buffalo.

Truly they made a gallant show

Across the prairie’s bright green flow,

Warriors painted indigo,

Brown antelope, black buffalo,

Long ago.

* * *

Now when he heard the barking of dogs, and saw the bundles of the dead lashed to the cottonwood trees, Many Swans knew that he was near a village. He stood still, for he dared not go on because of the thing which he had with him. He said to himself, “My mind is not strong enough to manage it. My mind is afraid of it.” But he longed to speak with men, and so he crept a little nearer until he could see the painted tepees standing in the edge of the sunshine, and smell the smoke of dried sweet grass. Many Swans heard the tinkling of small bells from the buffalo tails hung on the tepees, he saw the lodge ears move gently in the breeze. He heard talk, the voices of men, and he cried aloud and wept, holding his hands out toward the village.

Then the thing which he was carrying shook, and said: “We shall strike that town.” Many Swans heard it, and he tried to keep quiet. He tried to throw the thing down, but his hands closed. He could not keep his mind, and his senses flew away so that he was crazy. He heard a great voice shouting: “Break! Break! Break! Break!” but he did not know that it was his own voice.

Back over the prairie sprang up a round cloud, and fire rose out of the heart of the grass. The reds and yellows of the flowers exploded into flame, showers of sparks rattled on the metal sky, which turned purple and hurtled itself down upon the earth. Winds charged the fire, lashing it with long thongs of green lightning, herding the flames over the high grass; and the fire screamed and danced and blew blood whistles, and the scarlet feet of the fire clinked a tune of ghost-bells on the shells of the dry cane brakes. Animals ran — ran — ran — and were overtaken, shaken grass glittered up with a roar and spilled its birds like burnt paper into the red air. The eagle’s wing melted where it flew, the hills of the prairie grew mountain-high, amazed with light, and were obscured. The people in the village ran — ran — and the fire shot them down with its red and gold arrows and whirled on, crumpling the tepees so that the skins of them popped like corn. Then the bodies of the dead in the trees took fire with a hard smoke, and the burning of the cottonwoods choked Many Swans as he fled. His nostrils smelt the dead, and he was very sick and could not move. Then the fire made a ring round him, and he stood in the midst by the Burnt River and wrung his hands until the skin tore. He took the thing he wore and tried to strip it off in the fork of a tree, but it did not come off at all. He cried: “Ka! Ka! Ka! Ka!” and leapt into the river and tried to drown the thing, but when he rose it rose with him and came out of the water gleaming so that its wake rippled red and silver a long way down the stream.

Then Many Swans lamented bitterly and cried: “The thing I wanted is bad,” but he had the thing and he could not part from it. He rolled in the stones and the bushes to scrape it off, but it clung to him and grew in his flesh like hair. Therefore Many Swans dragged himself up to go on, although the heat of the burnt grass scorched his feet and everything was dead about him. He heard nothing, for there was nobody to mock any more.

* * *

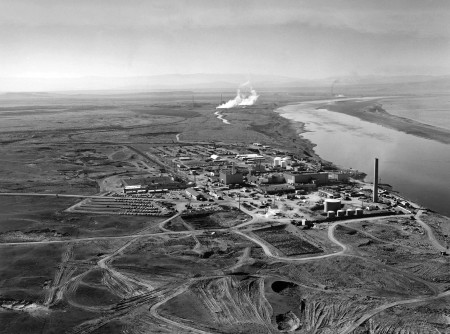

Mist rises along the river bottoms, and ghost-voices hiss an old death-song to a false, faint tune. The branches of willows beat on the moon, pound, pound, with a thin, far sound, shaking and shrilling the wonder tale, the thunder tale, of a nation’s killing:

The Nation’s drum has fallen down.

Beat — beat — and a double beat!

Ashes are the grass of a lodge-pole town.

Rattle — rattle — on a moon that is sinking.

Out of the North come drift winds wailing.

Beat — beat — and a double beat!

In the frost-blue West, a crow is ailing.

The streams, the water streams, are shrinking!

He gave an acre and we gave him brass.

Beat — beat — and a double beat!

Beautiful and bitter are the roses in the grass.

Rattle — rattle — on a moon that is sinking.

A knife painted red and a knife painted black.

Beat — beat — and a double beat!

Green mounds under a hackmatack.

The streams, the water streams, are shrinking!

Is there Summer in the Spring? Who will bring the South?

Beat — beat — and a double beat!

Shall honey drop from the green snake’s mouth?

Rattle — rattle — on a moon that is sinking.

A red-necked buzzard in an incense tree.

Beat — beat — and a double beat!

And a poison leaf from Gethsemane.

The streams, the water streams, are shrinking.

* * *

Now Many Swans walked over cinders, and there was no sprig or root that the fire had left. Therefore he grew weaker day by day, and at night he lay awake tortured for food, and he prayed to the Earth, saying: “Mother Earth have pity on me and give me to eat,” but the ears of the Earth were stopped with cinders. Then, after five sleeps, suddenly before him grew a bush of service-berries which the fire had not taken. Many Swans gathered the berries and appeased his hunger. He said: “The berries that grow are blessed, for now I shall live.” Yet he knew that he did not want to live, only his hunger raged fiercely within him and he could not stand against it. He took cinders and powdered them, and mixed them with river water, and made his body black, and so he set his back to the river and his face to the mountains and journeyed on.

Up and over the Backbone-of-the-World went Many Swans. Above the peaks of solitude hang the winds of all directions, and because there are a multitude of winds they can hold fire and turn it. Therefore Many Swans felt leaves once more about his face, and the place was kind to his eyes with laurels, and quaking aspens, and honeysuckle trees. All the bushes and flowers were talking, but it was not about Many Swans. The oaks boasted of their iron sinews: “Fire is a plaything, a ball to be tossed and flung away,” and they rustled their leaves and struck their roots farther into the moist soil. The red firs stirred at the challenge: “In Winter your leaves are dry,” they called to the oaks, “then the fire-bear can eat you. But our leaves are never dry. They are whips to sting the lips of all fires.” But the cedars and the pines said nothing, for they knew that nobody would believe them if they spoke.

Now when the hemlocks ran away from him, and the cold rocks glittered with snow, Many Swans knew that he stood at the Peak of the World, and again the longing for men came upon him. “I will descend into a new country,” he said. “I will be very careful not to swing the sacred implement, truly it kills people so that they have no time to escape.” He thought he could do it, he believed himself, and he knew no rest because of his quest for men.

There was no way to find, but Many Swans went down through the firs, and the yellow pines, and the maples, to a white plain which ran right, and left, and forward, with only a steep sky stopping it very far off; and the sun on the plain was like molten lead pressing him down and his tongue rattled with thirst. So he lifted himself against the weight of the sun and wished a great wish for men and went on with his desire sobbing in his heart.

To the North was sand, to the East was sand, to the West was sand, to the South was sand, and standing up out of the sand the great flutes of the cactus-trees beckoned him, and flung their flowers out to tempt him — their wax-white flowers, their magenta flowers, their golden-yellow flowers perking through a glass-glitter of spines; all along the ridges of the desert they called to him and he knew not which way to turn. He asked a humming-bird in a scarlet trumpet-flower, and the humming-bird answered: “Across the sunset to the Red Hills.” The sun rose and set three times, and again he knew not where to go, so he asked a gilded flicker who was clicking in a giant cactus. And the flicker told him: “Across the sunset to the Red Hills.” But when, after many days, he saw no hills, he thought “The birds deceived me,” and he asked a desert lily: “Where shall I find men?” And the lily opened her green-and-blue-veined blossom, and discovered the pure whiteness of her heart. “Across the desert to the Red Hills,” she told him, and he believed her, and, on the ninth morning after, he saw the hills, and they were heliotrope and salmon, and as the sun lifted, they were red, and when the sun was in the top of the sky, they were blood scarlet. Then Many Swans lay and slept, for he did not wish to reach the hills at nightfall lest the people should take him for an enemy and kill him.

* * *

In the morning, Many Swans got up and made haste forward to the hills, and soon he was among cornfields, and the rows of the cornfields were newly plowed and from them there came a sound of singing. Then Many Swans felt the fear come upon him because of the thing he loathed and yet carried, and he thought: “If it should kill these people!” The music of the song was so beautiful that he shed tears, but his fears overcame his longing, for already he loved these people who sang in cornfields at dawn. Many Swans hid in a tuft of mesquite bushes and listened, and the words the people were singing were these, but the tune was like a sun wind in the tree-of-green-sticks:

The white corn I am planting,

The white seed of the white corn.

The roots I am planting,

The leaves I am planting,

The ear of many seeds I am planting,

All in one white seed.

Be kind! Be kind!

The blue corn I am planting,

The blue ear of the good blue corn.

I am planting tall rows of corn.

The bluebirds will fly among my rows,

The blackbirds will fly up and down my rows,

The humming-birds will be there between my rows,

Between the rows of blue corn I am planting.

Beans I am planting.

The pod of the bean is in the seed.

I tie my beans with white lightning to bring the thunder,

The long thunder which herds the rain.

I plant beans.

Be kind! Be kind!

Squash-seeds I am planting

So that the ground may be striped with yellow,

Horizontal yellow of squash-flowers,

Horizontal white of squash-flowers,

Great squashes of all colours.

I tie the squash-plants with the rainbow

Which carries the sun on its back.

I am planting squash-seeds.

Be kind! Be kind!

Out of the South, rain will come whirling;

And from the North I shall see it standing and approaching.

I shall hear itdropping on my seeds,

Lapping along the stems of my plants,

Splashing from the high leaves,

Tumbling from the little leaves.

I hear it like a river, running — running —

Among my rows of white corn, running — running —

I hear it like a leaping spring among my blue corn rows,

I hear it foaming past the bean sprouts,

I hear water gurgling among my squashes.

Descend, great cloud-water,

Spout from the mouth of the lightning,

Fall down with the overturning thunder.

For the rainbow is the morning

When the sun shall raise us corn,

When the bees shall hum to the corn-blossom,

To the bean blossom,

To the straight, low blossoms of the squashes.

Hear me sing to the rain,

To the sun,

To the corn when I am planting it,

To the corn when I am gathering it,

To the squashes when I load them on my back.

I sing and the god people hear,

They are kind.

When the song was finished, Many Swans knew that he must not hurt this people. He swore, and even upon the sacred and terrible thing itself, to make them his safe keeping. Therefore when they returned up the trail to the Mesa, he wandered in the desert below among yellow rabbit-grass and grey iceplants, and visited the springs, and the shrines full of prayer-sticks, and his heart distracted him with love so that he could not stay still.

That night he heard an elf owl calling from a pinyon-tree, and he went to the owl and sought to know the name of this people who sang in the fields at dawn. The owl answered: “Do not disturb me, I am singing a love-song. Who are you that you do not know that this is the land of Tusayan.” And Many Swans considered in himself: “Truly I have come a long way.”

Four moons Many Swans abode on the plain, eating mesquite pods and old dried nopals, but he kept away from the Mesa lest the thing he had with him should be beyond his strength to hold.

* * *

Twixt this side, twixt that side,

Twixt rock-stones and sage-brush,

Twixt bushes and sand,

Go the snakes a smooth way,

Belly-creeping,

Sliding faster than the flash of water on a bluebird’s wing.

Twixt corn and twixt cactus,

Twixt springside and barren,

Along a cold trail

Slip the snake-people.

Black-tip-tongued Garter Snakes,

Olive-blue Racer Snakes,

Whip Snakes and Rat Snakes,

Great orange Bull Snakes,

And the King of the Snakes,

With his high rings of scarlet,

His high rings of yellow,

His double high black rings,

Detesting his fellows,

The Killer of Rattlers.

Rattle — rattle — rattle —

Rattle — rattle — rattle —

The Rattlers,

The Rattlesnakes.

Hiss-s-s-s!

Ah-h-h!

White Rattlesnakes,

Green Rattlesnakes,

Black-and-yellow Rattlesnakes,

Barred like tigers,

Soft as panthers.

Diamond Rattlesnakes,

All spotted,

Six feet long

With tails of snow-shine.

And most awful,

Heaving wrongwise,

The fiend-whisking

Swift Sidewinders.

Rattlesnakes upon the desert

Coiling in a clump of greasewood,

Winding up the Mesa footpath.

Who dares meet them?

Who dares stroke them?

Who dares seize them?

Rattle-rattle-rattle —

Rattle — rattle — hiss-s-s!

They dare, the men of Tusayan. With their eagle-whips they stroke them. With their sharp bronze hands they seize them. Run — run — -up the Mesa path, dive into the kiva. The jars are ready, drop in the rattlers — Tigers, Diamonds, Sidewinders, drop in Bull Snakes, Whip Snakes, Garters, but hang the King Snake in a basket on the wall, he must not see all these Rattlesnakes, he would die of an apoplexy.

They have hunted them toward the four directions. Toward the yellow North, the blue West, the red South, the white East. Now they sit by the sand altar and smoke, chanting of the clouds and the four-coloured lightning-snakes who bring rain. They have made green prayer-sticks with black points and left them at the shrines to tell the snake people that their festival is here. Bang! Bang! Drums! And whirl the thunder-whizzers!

“Ho! Ho! Ho! Hear us!

Carry our words to your Mother.

We wash you clean, Snake Brothers.

We sing to you.

We shall dance for you.

Plead with your Mother

That she send the white and green rain,

That she look at us with the black eyes of the lightning,

So our corn-ears may be double and long,

So our melons may swell as thunder-clouds

In a ripe wind.

Bring wind!

Bring lightning!

Bring thunder!

Strip our trees with blue-rain arrows.

Ho-Ho-hai! Wa-ha-ne”

Bang! Bang!

Over the floor of the kiva squirm the snakes, fresh from washing. Twixt this side, twixt that side, twixt toes and twixt ankles, go the snakes a smooth way, and the priests coax them with their eagle-feather whips and turn them always backward. Rattle — rattle — rattle — snake-tails threshing a hot air. Whizz! Clatter! Clap! Clap! Corn-gourds shaking in hard hands. A band of light down the ladder, cutting upon a mad darkness.

Cottonwood kisi flickering in a breeze, little sprigs of cotton-leaves clapping hands at Hopi people, crowds of Hopi people waiting in the Plaza to see a monstrous thing. Houses make a shadow, desert is in sunshine, priests step out of kiva.

Antelope priests in front of the kisi, making slow leg-motions to a slow time. Turtle-shell knee-rattles spill a double rhythm, arms shake gourd-rattles, goat-toes; necklaces — turquoise and sea-shell — swing a round of clashing. Striped lightning antelopes waiting for the Snake Priests. Red-kilted Snake Priests facing them, going forward and back, coming back and over, waving the snake-whips, chanting a hundred ask-songs. Go on, go back — white — black — red blood-feather, white breath-feather, little cotton-leaf hands clap — clap — He is at the flap of the kisi, they have given him a spotted rattlesnake. Put him in the mouth, kiss the Snake Brother, fondle him with the tongue.

Tripping on a quick tune, they trot round the square. Rattle — rattle — goat-toes, turtle-shells, snake-tails. Hiss oily snake-mouths, drip wide priest-mouths over the snake-skins, wet slimy snake-skins. “Aye-ya-ha! Ay-ye-he! Ha-ha-wa-ha! Oway-ha!” The red snake-whips tremble and purr. Blur, Plaza, with running priests, with streaks of snake-bodies. The Rain-Mother’s children are being honoured. They must travel before the setting of the sun.

* * *

When the town was on a roar with dancing, Many Swans heard it far down in the plain, and he could not contain his hunger for his own kind. He felt very strong because the cool of sundown was spreading over the desert. He said, “I need fear nothing. My arms are grown tough in this place, my hands are hard as a sheep’s skull. I can surely control this thing,” and he set off up the path to ease his sight only, for he had sworn not to discover himself to the people. But when he turned the last point in the road, the thing in his hands shook, and said: “We shall strike that town.”

Many Swans was strong, he turned and ran down the Mesa, but, as he was running, a priest passed him carrying a handful of snakes home. As the priest went by him, the thing in Many Swan’s hand leapt up, and it was the King Snake. It was all ringed with red and yellow and black flames. It hissed, and looped, and darted its head at the priest and killed him. Now when the priest was dead, all the snakes he was holding burst up with a great noise and went every which way, twixt this side, twixt that side, twixt upwards, twixt downwards, twixt rock-stone and bunch-grass.

And they were little slipping flames of hot fire. They went up the hill in fourteen red and black strings, and they were the strings of blood and death. The snakes went up a swift, smooth way and Many Swans went up with them, for he was mad. He beat his hands together to make a drum, and shouted “Break! Break! Break! Break!” And he thought it was the priests above singing a new song.

Many Swans reached the town, but the fire-snakes were running down all the streets. They struck the people so that they died, and the bodies took fire and were consumed. The house windows were hung with snakes who were caught by their tails and swung down vomiting golden stars into the rain-gutters. In one of the gutters was a blue salvia plant, and, as Many Swans passed, it nodded and said “Alas! Alas!” It reminded Many Swans of the flax-flowers in the sky, and his senses came back to him and he tore his clothes and his hair and cried “Ka! Ka! Ka! Ka!” a great many times. Then he beat himself on the sharp rocks and tried to crush the thing he had, but he could not; he tried to split it, but it did not split.

Many Swans saw that he was alone in the world. He lifted his eyes to the thing and cursed it, then he ran to hurl himself over the cliff. Now a boulder curled into the path and, as he turned its edge, The-One-Who-Walks-All-Over-the-Sky stood before him. Her eyes were moons for sadness, and her voice was like the coiling of the sea. She said to him: “I tried to love you; I tried to be kind to your people; why do you cry? You wished for it.” She took it off him and left him.

Many Swans looked at the desert. He looked at the dead town. He wept.