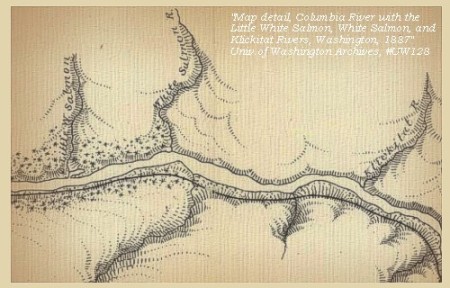

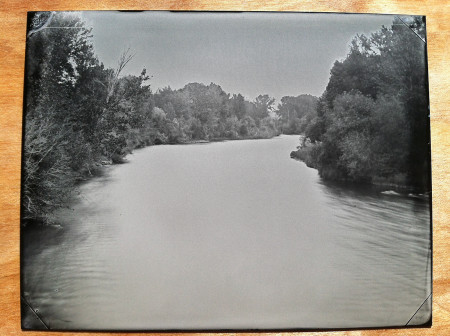

Hassalo ran on the “Middle” Columbia river, that is, the reach between the Cascades and the Dalles, Oregon.

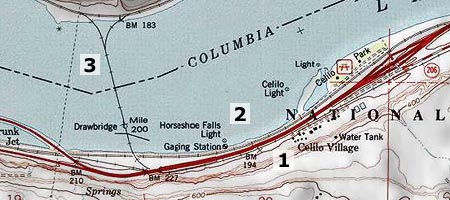

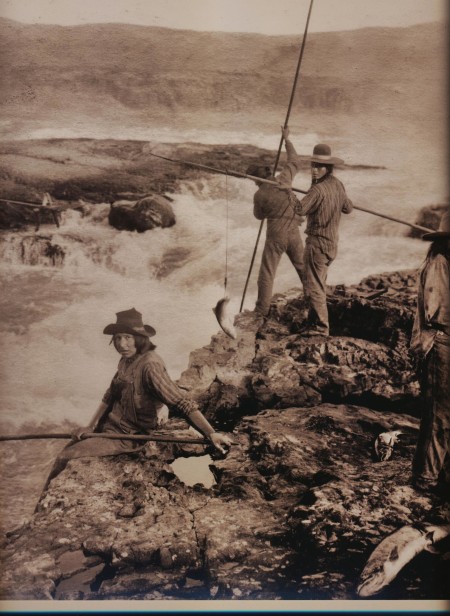

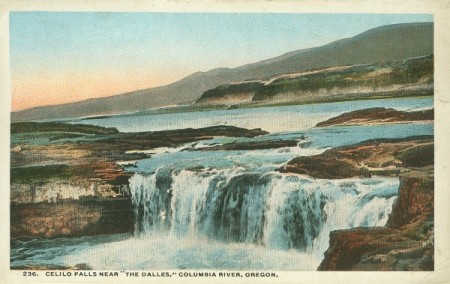

The Columbia river was only freely navigable up to the Cascades of the Columbia, a stretch of rapids in the Columbia Gorge that has since been submerged by water pooling behind Bonneville Dam. Above the Cascades there was a stretch of navigable river going east about 40 miles (64 km) to The Dalles. This reach was called the “Middle River.” After that, navigation was further impeded by a longer series of rapids, the most important of which was Celilo Falls.

Before rail lines were built, travellers bound from Portland, Oregon for Idaho or the Inland Empire generally went by way of the Columbia River. This route was like a series of giant stair steps.

First, traffic proceeded by steamboat up to the Cascades, where rapids blocked the river to all upstream traffic and made downstream traffic extremely hazardous. This then required transfer to a portage railroad (first hauled by mules, later by steam engines), which proceeded to the top of the Cascades. Travellers then boarded another steamboat to proceed up river to the Dalles, where the process would be repeated for a 13-mile (21 km) portage around Celilo Falls and the other rapids upriver from the Dalles, which like the Cascades were unnavigable both upstream and downstream. This, the middle river, was the route Hassalo ran on from 1880 to 1888.

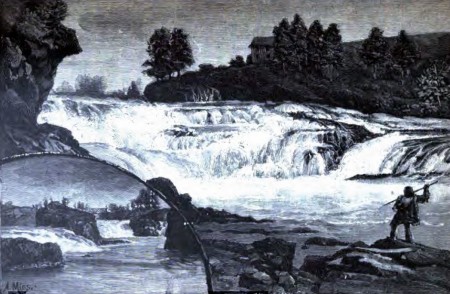

As railways began to be completed along the banks of the Columbia, the steamboats, tied to the river which required too much loading and unloading of passengers and cargo, proved to be unable to compete, and one by one they were taken off the Middle River. The turn of the Hassalo came on Saturday, May 26, 1888, under the command of Captain James W. Troup. The event had been announced well in advance, and three thousand people gathered along the banks of the Columbia to watch. The channel through the Cascades was six miles (10 km) long.

As railways began to be completed along the banks of the Columbia, the steamboats, tied to the river which required too much loading and unloading of passengers and cargo, proved to be unable to compete, and one by one they were taken off the Middle River. The turn of the Hassalo came on Saturday, May 26, 1888, under the command of Captain James W. Troup. The event had been announced well in advance, and three thousand people gathered along the banks of the Columbia to watch. The channel through the Cascades was six miles (10 km) long.

The Northwest Masters and Pilots Association organized two steamers, the R.R. Thompson and the Lurline to bring crowds up from Portland and Vancouver to witness the event. Describing the excursion up river, the Sunday Oregonian wrote:

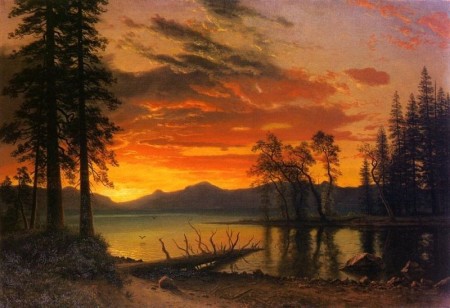

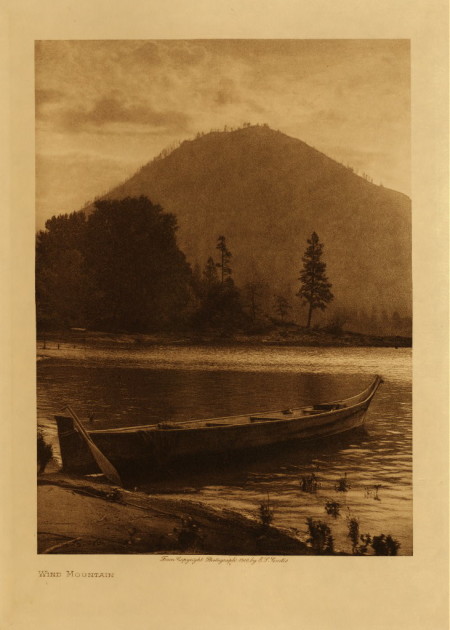

Fully 1500 persons were on the ride up the noble majestic stream was an enchanting one. The day was perfect as to temperature, and the scenery was grand; every bend and turn of the river disclosed superb views of mountain, forest and water scenery not surpassed on the entire American continent. Field and marine glasses were in ready demand, and hundreds crowded the decks and admired the grand panorama as it passed swiftly by.

The excursion boats arrived at the Cascades, and the excursionists disembarked on the north, Washington Territory side. There was a scramble up the bank to board the portage train which was to take the crowd to the Upper Cascades where the run was to start. There weren’t enough seats on the train, so a part of the crowd had to wait for the train to run up to the Upper Cascades and return. People had also come down from The Dalles on the Harvest Queen, which ran down to the Cascades with the Hassalo. Other people came up on a train from Bonneville so that there were about 3,000 excursionists overall. As the crowds assembled, both Hassalo and Harvest Queen were at the Upper Cascades wharf with all flags flying. When everything was finally ready, the scene was described by the Sunday Oregonian’s correspondent:

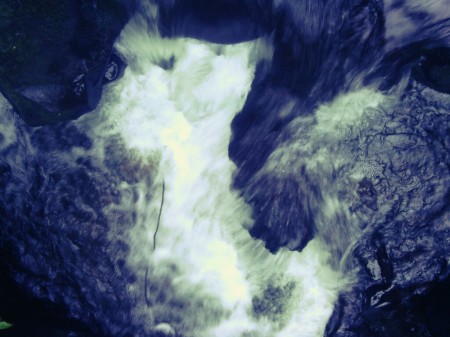

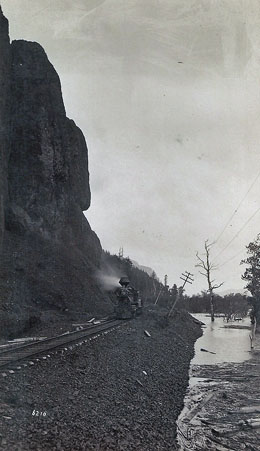

Six loud whistles were given by the locomotive as a signal to the Hassalo that all was ready. … A moment later the Hassalo’s wheel was seen beating the water into foam. She moved gracefully from the wharf, swung round deliberately [.] … [W]ith her sharp glistening prow aimed at the great roaring breach, she shot toward the green rolling masses. From shore to shore the first line of the rapids stretched like a cordon of breakers, and thundering like the tumultuous surf. With a full head of steam, the Hassalo entered the upper break in the waters, and here receiving the first impulse of the mighty current, made a plunge that thrilled the crowd as if touched by an electric shock. ‘There she goes’, exclaimed a thousand voices in low, subdued tones. Crossing the break the steamer rose pointing her bow upward at a sharp angle, and then blindly plunged downward as if going to the bottom; but she came up with the buoyancy of a cork, and now having committed herself to the mercy of the rapids, flew with the speed of an arrow through and over the surging, boiling waters.

Hassalo with just 15 people on board, passed by the people on the bank in just 30 seconds and disappeared from sight around a bend in the river. As she ran down the rest of the six mile (10 km) run, she exchanged whistle blasts with locomotives on the railway tracks besides the river. Once at the end of the rapids, which she ran in seven minutes, Captain Troup took Hassalo down the Columbia and up the Willamette River to Portland.

Remarkable as this was, even the run of Hassalo was not the fastest through the Cascades. On June 3, 1881, captain Troup had taken R.R. Thompson (sternwheeler), one of the same boats that was to run on the Hassalo excursion seven years later, through the Cascades, completing the run twenty seconds faster, and this speed was bested exactly one year later by the R.R. Thompson, itself, when, then, under the mastery of the earlier mentioned and unrivaled riverboatman, Captain John McNulty (steamboat captain). For those times there were not 3,000 people to watch, nor was a famous photograph taken, so the R.R. Thompson runs are largely forgotten by history.

(http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hassalo_%28sternwheeler_1880%29)