In 1988, during my time in middle school, my US history teacher delivered the news to the class that the Cascade/ Watala tribes residing along the Columbia River were no longer in existence because they did not have a reservation. This revelation struck a chord within me, as I felt deeply connected to the stories of my ancestors, both in flesh and spirit. In response to this declaration, I boldly asserted that we were not extinct, but rather transformed. This pivotal moment opened my eyes to a profound sense of self, one intrinsically intertwined with the land and the crucial presence of the Salmon, a keystone species. It was an identity forged out of defiance against the encroachment of settler colonialism and the reservation system that sought to uproot us from our sacred river. From the initial encounters with settlers to the present day, settler colonialism has irrevocably reshaped the physical and cultural landscapes along the Nch’i-Wanna (Columbia River).

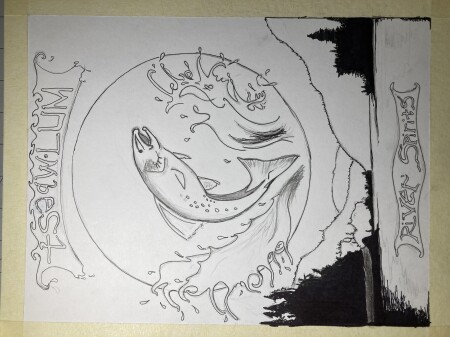

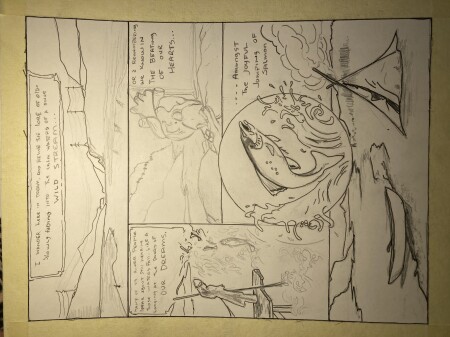

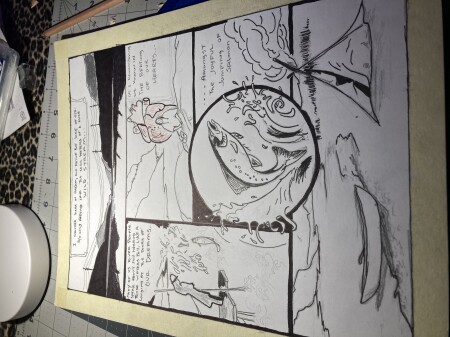

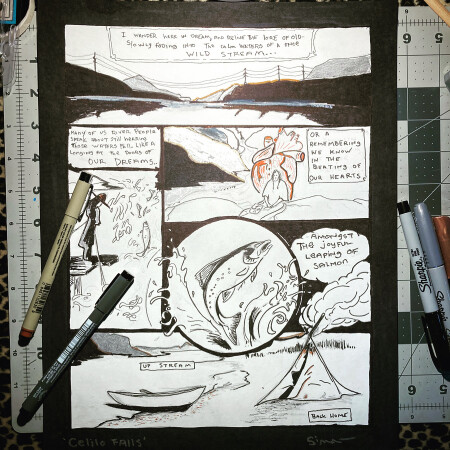

Throughout history, the Nch’i-Wanna has served as the ancestral homeland for various indigenous groups such as  the Watala/ Cascade, Wishram-Wasco, Klickitat, Yakima, Wanapum, and others. Despite their differences, these diverse cultures shared a deep connection with the river and its abundant Salmon. Ancient legends speak of Coyote bestowing the gift of Salmon upon the River People. The Salmon, in turn, carried the hopes and prayers of countless generations, swimming upstream to their birthplace at the Cascades Rapids (which gave the Cascade Mountains their name), passing through The Dalles straits, and continuing on to Wyam, also known as Celilo Falls, and beyond. Each spring, thousands would gather along the mighty river to celebrate the arrival of the first Salmon. They would sing songs, engage in trade, play stick games, and forge strong bonds of kinship. These vibrant cultures held a deep reverence for the natural world and had a profound sense of place. Traditional ceremonies like the Feather Religion were conducted to honor and express gratitude to the natural world. These cultural practices play a vital role in preserving the identity and heritage of the Columbia River Indians. They are a people who have chosen to live outside the confines of reservations and forced relocation, instead embracing the ways of their ancestors and the lifeways of the Big River.

the Watala/ Cascade, Wishram-Wasco, Klickitat, Yakima, Wanapum, and others. Despite their differences, these diverse cultures shared a deep connection with the river and its abundant Salmon. Ancient legends speak of Coyote bestowing the gift of Salmon upon the River People. The Salmon, in turn, carried the hopes and prayers of countless generations, swimming upstream to their birthplace at the Cascades Rapids (which gave the Cascade Mountains their name), passing through The Dalles straits, and continuing on to Wyam, also known as Celilo Falls, and beyond. Each spring, thousands would gather along the mighty river to celebrate the arrival of the first Salmon. They would sing songs, engage in trade, play stick games, and forge strong bonds of kinship. These vibrant cultures held a deep reverence for the natural world and had a profound sense of place. Traditional ceremonies like the Feather Religion were conducted to honor and express gratitude to the natural world. These cultural practices play a vital role in preserving the identity and heritage of the Columbia River Indians. They are a people who have chosen to live outside the confines of reservations and forced relocation, instead embracing the ways of their ancestors and the lifeways of the Big River.

Magic of Place written in stone.

In this post, we will examine a timeline of immense changes that created and molded the Columbia River Indian

identity. Starting with an overview of pre-contact life along the Columbia River, we will examine the culture of stories and place that informed the Ancestors space in the cosmos and how violently that changed after first contact. We will look at how that first contact was a sight unseen as pestilence decimated a People who had never known such a thing. Animist cultures who internalized the settler crisis on a spiritual level, creating a “spiritual apocalypse” across the Columbia River basin, where Dreamer Prophets arose with promises of deliverance from the settlers disease, violence and reservations that tore kinship ties apart. We will look at how the term “renegade Indian” became synonymous with the Columbia River Indian, and how resistance to settler colonialism continues to this day. We are not extinct, only transformed.

I. Pre-Contact to First Contact: Prehistoric Life on the Mid-Columbia River and the Coming Storms of Pestilence

“Long ago, when the world was young, all people were happy. The Great Spirit, whose home is in the sun, gave them all they needed. No one was Hungry, no one was cold. But after a while, two brothers quarreled over the land. The elder one wanted most of it, and the younger one wanted most of it. The Great Spirit decided to stop the quarrel. One night while the brothers were asleep he took them to a new land, to a country with high mountains. Between the mountains flowed a big river .” - Keeper of Fire, Bridge of the Gods Legend

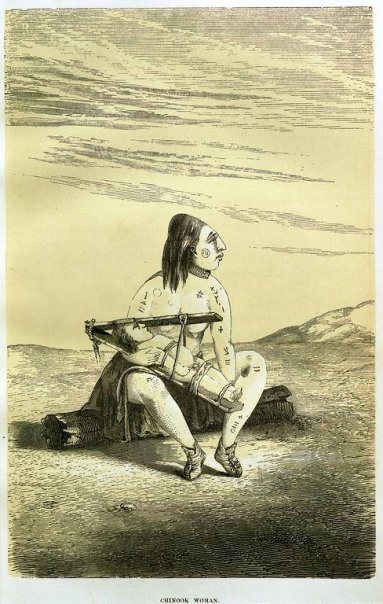

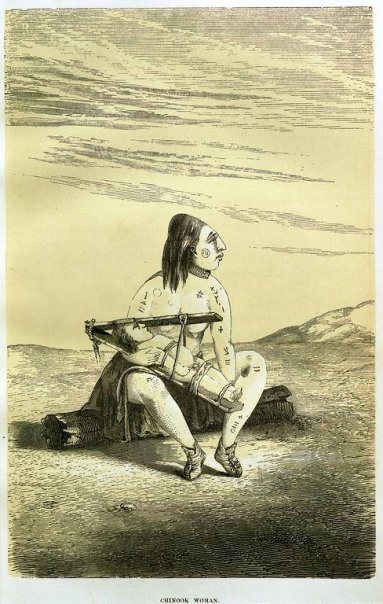

Paul Kane drawing of one of my Watala/ Chinook ancestors.

The Nch’i-Wanna has woven tales from the depths of volcanoes and the frozen expanse of ice through its elaborate ritual of creation. For ages untold, the mythologies surrounding the Columbia River basin have spoken of the profound reverence the People hold for this wild and picturesque landscape, often described “in poetic expression and high drama” (Hunn & Selam, 1990, p. 7). Stretching from the arid high desert plains of the upper Nch’i-Wanna to the verdant rainforests of the lower region, this mighty river has acted as a lifeline connecting various cultures, united by the abundance of Salmon. The indigenous tribes residing in the Mid-Columbia area skillfully utilized the bountiful salmon harvest in combination with plentiful root foods to sustain a substantial population, enabling the establishment of large winter settlements and summer gatherings that numbered in the thousands. (Hunn & Selam, 1990, p. 6). The land itself shaped the identity and way of life for the Mid-Columbia Indigenous people, permeating every aspect of their existence.

When Lewis and Clark made their westward voyage in 1804-05 they came across a Peoples who were already dealing with the effects of European contact with the spread of the smallpox epidemic among Pacific Northwest tribes in 1781. (Boyd, 2021) These epidemics swept through with a fury, altering the lives of thousands in a matter of a blink. It was endemic of what was ahead for the Columbia River Indians with the coming wave of settler colonialism. The epidemics began breaking down traditional tribal identities early on, cutting the population in about one half by 1801, yet the smallpox was just the beginning of the pestilence that would engulf Columbia River Indians. In the 1820’s, a Wasco prophet was reported to have had a vision that foresaw a day when many Indigenous People would “lay dead like driftwood along the shores of the [Big River].” (Fisher, 2011, p. 28) That vision became true just a few years later.

Fort Vancouver, HJ Ware, 1848

In the summer of 1830 “fever and ague”, also known as Malaria, broke out at the Hudson Bay’s headquarters of Fort Vancouver which decimated Chinookian villages of the lower Columbia. (Hunn & Selam, 1990, p. 27) These epidemics took more lives than all of the warfare provoked by settler colonialism and proved to further erode and eradicate kinship ties and families and create a void of identity among the Columbia River Indians as the story tellers, the elders, and the medicine people began to die and whole villages disappeared. (Fisher, 2011, p. 28) The storms had arrived and the stage had been set for an invasion that would alter the landscapes of the Big River forever.

II. “Spiritual Apocalypse” and the Making of the Dreamer Prophets

Tsagaglalal (She Who Watches) is said to be a death mask, a warning of pestilence

As the onslaught of settlers to the Columbia River Basin dredged a new paradigm of disease and displacement, there was what Hunn describes as a “spiritual apocalypse” among the River People. (Hunn & Selam, 1990, p. 241) A “spiritual apocalypse” where animist cultures struggled with the biological reality of disease, for there had to be a spiritual reason for the trauma- something must be out of alignment with the spirit. Elizabeth Vibert describes in her journal article “The Natives Were Strong to Live”: Reinterpreting Early-Nineteenth-Century Prophetic Movements in the Columbia Plateau”:

In the first two contact-era Plateau epidemics (I770s and 18oo-i), there is much to indicate that illness and death were not blamed on outside contagion. The peoples of the region turned inward for explanation. Smallpox, and other serious diseases, signaled an imbalance or power struggle among the personal spirit partners that animated the spiritual universe of the Plateau. Smallpox was read as a spiritual crisis within Plateau societies, and the prophetic movements of the time were an attempt to stem that crisis. (Vibert, 1995, p. 4)

These prophetic movements were a grounding force within the Columbia River Indians cosmology. A way to bring sense to their changing world and align themselves with the wisdom of their elders, and to bring them back to life to help aid in restoration of traditional lifeways.

One of the earliest accounts of a plateau prophet traveling to the mid-Columbia region was that of Kaúxuma núpika, an indigenous transgender prophet living on the Columbia Plateau in the early nineteenth century. Kaúxuma núpika traveled the length of the Columbia River, prophesying a coming apocalypse and the destruction of Native people by epidemic diseases brought by Euro American settlers. (Crawford O’Brien, 2015, p. 4) These prophecies resonated strongly with the River People, and was the beginning of creating the renegade spirit that would define the Columbia River Indian character as the settler apocalypse sharpened its teeth. Although Kaúxuma núpika hit a chord with the People, it would not be until the prophet Smohalla and his Dreamer Religion would emerge in the 1850’s that the Columbia River Indian would claim a spiritual resistance to the settler apocalypse.

Chief Smohalla

Conceived around 1815 in a Wanapum village along the Columbia River, Smohalla was born during a time of great upheaval for his People. Smohalla would have profound visions and dreams during death like sleeps where he would profess to talk to the dead and receive instructions from Creator. He amassed loyal disciples with his decree called Wa-sani (Washani, meaning “dancers” or “worship”). They believed that Indians must stop tilling the soil or face divine retribution. To obey the creed and faithfully perform the wa-sat (“dance”) meant the Creator would reward the People by making the whites die off or disappear, deceased relatives would return to life, and the land would revert to its pristine state from before first contact. (Fisher, 2011, p. 84) Smohalla’s prophecies spoke directly to the renegade spirit of the Columbia River Indians, and would prove to be a thorn in the side of the reservation system that was emerging from the settler apocalypse.

III. “Nurseries of Civilization”: Diaspora, Reservations, and Resistance Along the Big River and the Emergence of the Columbia River Indian Identity.

“Where will we go? Where will we make our homes? If we lose our country what shall we do?”- William Chinook (Fisher, 2011, p. 37)

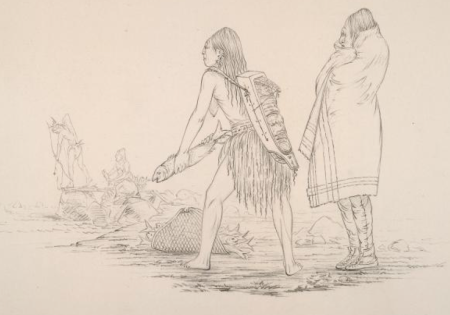

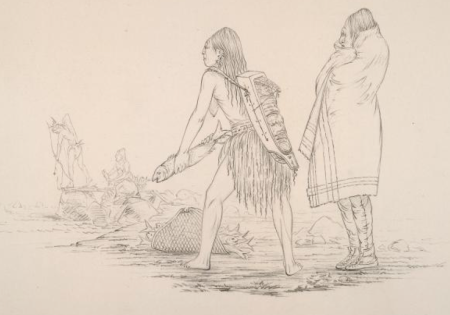

At The Dalles, George Catlin. 1850

As if the apocalyptic pestilence of disease had not been enough, the coming storms of settler invaders brought with them further demands on resources; cultural, ecological, and biological resources became a desperate diaspora of survival for the Columbia River Indian. As more and more settlers moved in for the promiseland of Oregon, they brought with them the idea of taming the Indian from the land. The new paradigm demanded the Indian fit into “a suitable tribal taxonomy”(Fisher, 2011, p. 38) that was carefully curated between 1846-1855 based upon the ethnic stratification of the forty years previous. Forty years of broken family units, social bonds, and death created a “suitable tribal taxonomy” ripe to become the “nursery of civilization” and the birth of the reservation system along the Columbia River Basin. These stratifications were not just distinguished between generalized material culture and language, but were also gathered under a banner of “character”. Stereotypes of River People being “thieves”, for instance, would help sway settler popular opinions about the need to have them removed from their homelands. These forms of social control are endemic of a settler colonial framework, and have continued to help aid imperial United States foreign policy to this day. It is much easier to control those you deem as a problem/ different.

Treaty Lands

Flash ahead to that day in 1988 when my US History teacher tells us that my people are extinct- “a once noble and stoic savage now void from the place of their ancestors”. Yes, as far as a tribal distinction drawn up from settler colonial constructs are concerned, it would look as though we are extinct and landless. But, I am an enrolled Cowlitz, a cousin is an enrolled Yakama, another cousin is an enrolled Warm Springs, and my Greatx5 grandfather, Chief Tumulth, was a signer of the 1855 Kalapuya treaty- a treaty that threw us onto the Grande Ronde reservation in the soggy rainforest of the Oregon Coast Range- far from our traditional fishing grounds. Yet, at the core- we are of the Big River. These lines were drawn up out of the need for settler colonial interests to rid the land of the “Indian problem”, a “problem” they perceived to hinder the progress of a “civilized society” adherent to a single religion. This cognitive dissonance along the Big River really started to explode in the 1840’s, and the renegade Indian was emerging, unwilling to leave the life that was created for them by their ancestors and by the land as the state hurried its insatiable need for land and power.

Congress passed two pieces of legislation that unabashedly favored whites over Indians in the 1850’s. Starting in 1850 with the Oregon Donation Land Act, a piece of legislation that proclaimed that every adult male citizen could claim 320 acres from the public domain, and then with The Indian Treaty Act of 1850, which conveniently robbed the Indigenous People of their ancestral homelands and their removal to reservations to pave the way for a settler land grab.(Fisher, 2011, p. 40) These blatant racist policies of land theft and removal had no intention of honoring the cultural diversity of the Big River, only to further imaginary cultural lines that had nothing to do with the living cultures who were stuck in a desperate loop of survival. That survival was paramount to the Columbia River Indian- a survival that required them to live the life of their ancestors and to restore the land to its original pristine condition- just as Smohalla had instructed them. A land where the Salmon gifted all they needed.

Yakama Wars of 1855

A unified resistance was beginning to form in the early 1850’s, as Yakama headmen attempted to join their independent villages in a loose alliance that could better resist Suyapu encroachment. (Fisher, 2011, p. 41) These alliances began to monitor and discuss what was happening west of the Cascade Mountains as Governor Stevens quickly ratified several treaties by 1854. That same year, a large intertribal council with leaders from many Indigenous groups met in central Oregon to discuss a strong and unified resistance, maybe even armed, against the settler colonial expansionist empire of the United States. This spirit of resistance to Governor Stevens’ expectations was apparent among the Columbia River Indians, who would refuse to give up their autonomy and self sufficiency in his 1855 push to relocate them to reservations.

The general view of Indigenous Peoples along the Big River by settlers was that there was no such thing as a good or neutral Indian. The conflicts that were arising around the PNW at the time would be viewed as an organized and cohesive resistance to settlers, which was only intensified by the newspaper’s propaganda at the time. This culture of fear would lead to much violence provoked by settlers towards Indians. Just like with much of the United States at the time, volunteer vigilante militia groups would use excessive violence with the Indigenous populations of the Oregon territory. The violence fueled fear among the population, forcing many to the confines of reservations in hopes of escaping it. (Fisher, 2011, p. 57-58) This dichotomy would fuel a division among Indians, a division of traitors vs. traditionalists. The injustices that occurred in the seizing of lands and falsifying of treaties during the 1850’s even made the Governor cringe, even recommending that a new one be written up and ratified with the tribes. This recommendation was all but ignored when the senate ratified all treaties written four years earlier in 1859. “Mid-Columbia Indians accepted or rejected the treaties on their own terms, and continued to think of themselves as members of extended families and autonomous villages rather than constituents of confederated tribes.” (Fisher, 2011, p. 59) The 1850’s was a signal post to a greater sense of identity and a loose designation as Columbia River Indians that will accumulate recognition in the decades to come. All the while, the Salmon came and the River ran its seasonal cycles.

*****************************************

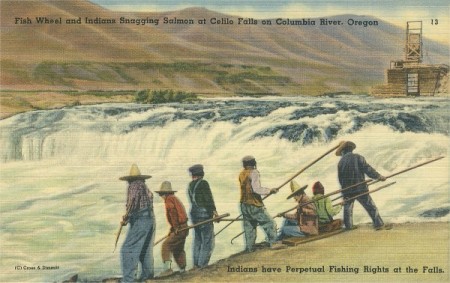

Columbia River Indian Family at Celilo Falls

The River People were pacifists. Even as senseless, racist violence was bestowed upon them- they would not wage war against anyone during the Yakama wars because of their firm belief and religious conviction they had learned from their ancestors, and through the words of Smoholla, the dreamer prophet. Although most River People claimed neutrality during the Yakama wars, Indian Office officials soon learned that it was not a sign of concession, as “defiance of federal power and distrust of tribal authority” became “hallmarks of Columbia River Indian Identity.” (Fisher, 2011, p.61) This “distrust of tribal authority” would only deepen as time progressed. And the berries would come as the Salmon was dried for the winter villages.

The reservation system was an attempt to keep Indians contained, but the seasonal lifeways and kinship ties that had been practiced for millenia would not keep River People contained. This autonomy and mobility would frustrate the powers that be, unable to know for sure how many “reservation Indians” they had “contained”. Agent James Wilbur would judge the “wandering vagrant Columbia River Indians” as folks who would only come to “subsist upon their more provident relatives.” (Fisher, 2011, p.65) The traveling, reservationless Columbia River Indian became known as “renegades”, always to live outside the lines of containment- but within the lines of their ancestral duties to the land and kin.

Settler colonial demands that had created the “spiritual apocalypse” a short 60 years prior had failed to deter old lifeways from extinction. We often speak of resilience here in “Indian Country”, not because we wish we had it, but because without it, we would not be here today. This resilience was the lifeblood of a people who lived tied to the cycles of a Big River- and with big hearts, would continue to resist and fight off the dragons so intent on destruction. The resilience of watching your people perish and still awake with love in your heart is strength beyond measure. This resilience, this strength, this resolve to exist along the Big River is the benchmark of what it meant and means to be a Columbia River Indian. This resolve would continue to get us targeted as “renegades”, and by the 1870’s would land us the official government correspondence title as “Columbia River Indians”. (Fisher, 2011, p.68)

IV. Conclusion

That pivotal day in 1988 woke me up to the complexity of our identities along the

Nch’i-Wanna which was formed out of the “spiritual apocalypse” of settler colonialism. An identity forged with resilience and resolve to keep the Ancestors memories alive and practice the old ways. Settler colonialism did not drive us extinct, it only transformed us- a transformation that continues to this day.

References

Boyd, R. (2021, December 10). The first epidemics: How disease ravaged Indigenous Northwest peoples. The Seattle Times. https://www.seattletimes.com/opinion/the-first-epidemics-how-disease-ravaged-indigenous-northwest-peoples/

Crawford O’Brien, S. (2015). Gone to the Spirits: A transgender prophet on the Columbia Plateau. Theology & Sexuality, 21(2), 125–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/13558358.2016.1215033

Fisher, A. H. (2011). Shadow tribe: The making of columbia river indian identity. University of Washington Press.

Hunn, E. S., & Selam, J. (1990). Nch’i-wána, “the big river”: Mid-Columbia indians and their land. University of Washington Press.

Vibert, E. (1995). “The natives were strong to live”: Reinterpreting early-nineteenth-century prophetic movements in the columbia plateau. Ethnohistory, 42(2), 197. https://doi.org/10.2307/483085

the Watala/ Cascade, Wishram-Wasco, Klickitat, Yakima, Wanapum, and others. Despite their differences, these diverse cultures shared a deep connection with the river and its abundant Salmon. Ancient legends speak of Coyote bestowing the gift of Salmon upon the River People. The Salmon, in turn, carried the hopes and prayers of countless generations, swimming upstream to their birthplace at the Cascades Rapids (which gave the Cascade Mountains their name), passing through The Dalles straits, and continuing on to Wyam, also known as Celilo Falls, and beyond. Each spring, thousands would gather along the mighty river to celebrate the arrival of the first Salmon. They would sing songs, engage in trade, play stick games, and forge strong bonds of kinship. These vibrant cultures held a deep reverence for the natural world and had a profound sense of place. Traditional ceremonies like the Feather Religion were conducted to honor and express gratitude to the natural world. These cultural practices play a vital role in preserving the identity and heritage of the Columbia River Indians. They are a people who have chosen to live outside the confines of reservations and forced relocation, instead embracing the ways of their ancestors and the lifeways of the Big River.

the Watala/ Cascade, Wishram-Wasco, Klickitat, Yakima, Wanapum, and others. Despite their differences, these diverse cultures shared a deep connection with the river and its abundant Salmon. Ancient legends speak of Coyote bestowing the gift of Salmon upon the River People. The Salmon, in turn, carried the hopes and prayers of countless generations, swimming upstream to their birthplace at the Cascades Rapids (which gave the Cascade Mountains their name), passing through The Dalles straits, and continuing on to Wyam, also known as Celilo Falls, and beyond. Each spring, thousands would gather along the mighty river to celebrate the arrival of the first Salmon. They would sing songs, engage in trade, play stick games, and forge strong bonds of kinship. These vibrant cultures held a deep reverence for the natural world and had a profound sense of place. Traditional ceremonies like the Feather Religion were conducted to honor and express gratitude to the natural world. These cultural practices play a vital role in preserving the identity and heritage of the Columbia River Indians. They are a people who have chosen to live outside the confines of reservations and forced relocation, instead embracing the ways of their ancestors and the lifeways of the Big River.