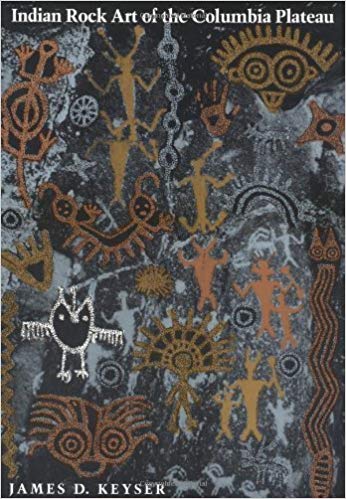

Written by: James D. Keyser, Indian rock art of the Columbia Plateau

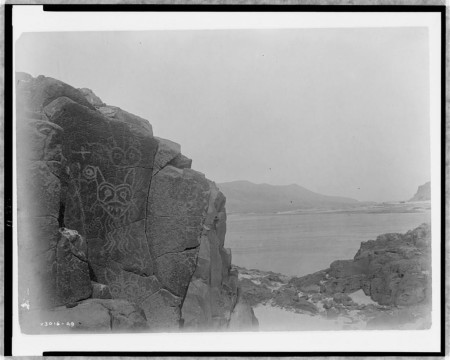

Rock art is one of the most common types of archaeological site in Oregon, occurring from the Portland Basin to Hell’s Canyon and the high desert canyons along the Owyhee River to far southwestern Oregon’s Rogue River drainage. Including both pictographs (paintings) and petroglyphs (carvings), the rock art at these sites was created as early as 7,000 years ago until as recently as the late 1800s. Although petroforms—a third type of rock art composed of outlines cut in desert pavement or boulders laid out in the form of animals or humans—are found elsewhere in North America, none has been discovered in Oregon.

Including both pictographs (paintings) and petroglyphs (carvings), the rock art at these sites was created as early as 7,000 years ago until as recently as the late 1800s. Although petroforms—a third type of rock art composed of outlines cut in desert pavement or boulders laid out in the form of animals or humans—are found elsewhere in North America, none has been discovered in Oregon.

Archaeologists have classified Oregon’s rock art into five traditions, that is, spatially broad-based artistic expressions that were created during a defined period of time. The traditions generally follow Oregon’s aboriginal ethnic/cultural boundaries. Thus, the Columbia Plateau Tradition reflects the art of Sahaptian-speaking tribes such as the Tenino, Nez Perce, Umatilla, and Klamath-Modoc, while the Great Basin Tradition comprises the art of the Numic-speaking bands of the Northern Paiute. In the river valleys of western Oregon, the few sites that are known represent the Columbia Plateau Tradition and a little-known California rock art expression called the Far Western Pit and Groove Tradition, which is the product of Tututni and Kalapuya artists and probably members of other tribes as well.

Cover to book text is from.

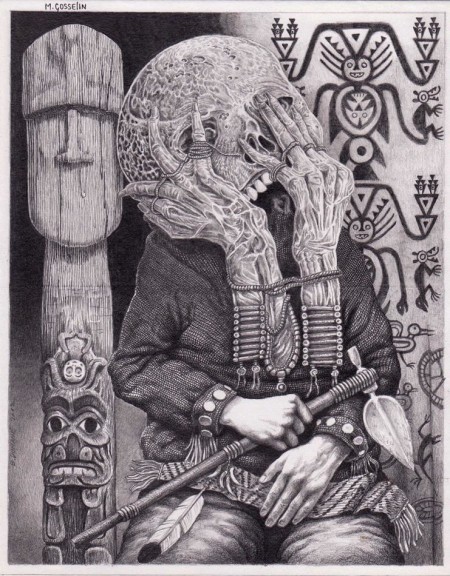

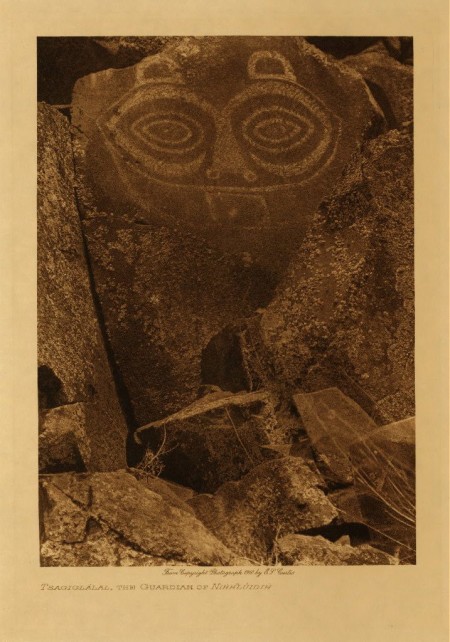

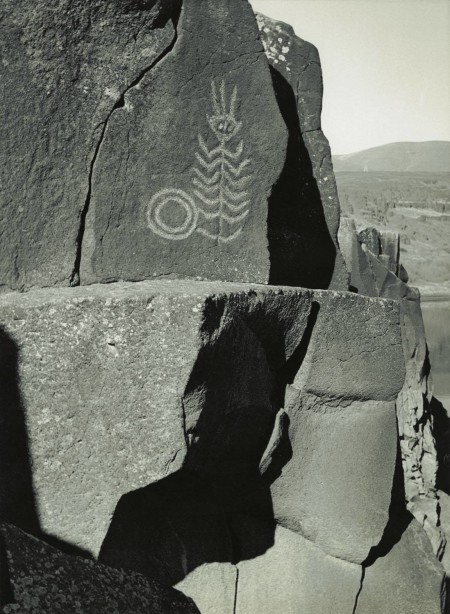

The subject matter of rock art in the Columbia Plateau Tradition is primarily humans, animals, and geometric designs, one of the most common of which is tally marks—a horizontally oriented series of three to more than thirty short, vertical, evenly spaced, finger-painted lines. Despite its limited subject matter, Columbia Plateau art functioned in several ways, including as a commemoration of the acquisition of spirit power during a vision quest and as a shaman’s ritual expression of power.

Yakima Polychrome designs and the closely related imagery of the Columbia River Conventionalized Style of the Northwest Coast Tradition served in healing and mortuary rituals and were used to witness mythic beings and places. Some images of animals and hunters in the Columbia Plateau Tradition were painted and carved as hunting magic. In the Klamath Basin, art in the Columbia Plateau Tradition has several stylistic expressions, but current research suggests that all of them were the exclusive purview of shamans.

Columbia River Gorge

Far Western Pit and Groove Tradition rock art is found from the southern Willamette Valley near Eugene into the Umpqua and Rogue River drainages, where it occurs as cupules—shallow dimples—and simple geometric forms pecked and ground into streamside boulders. Known as Baby Rocks or Rain Rocks, ethnographic sources indicate that these simple petroglyphs were carved both by shamans accessing and using supernatural power to call the salmon and communicate with the gods and by women who wanted to bear a child.

Vantage, WA.

Certainly much Great Basin rock art was made by shamans who were acquiring or using supernatural power, and much of the geometric imagery may have been generated in the artists’ minds by stimuli experienced during a trance. Other Great Basin imagery, however, is likely to have been made in conjunction with subsistence activities during the seasonal round of these high-desert hunter-gatherers and likely had a broader function as part of the rituals associated with subsistence.

God call them home? The few survivors walked away dazed. Took to speaking other languages. Were replaced by strangers. After a few decades hardly anyone remembered that they had ever been there.”

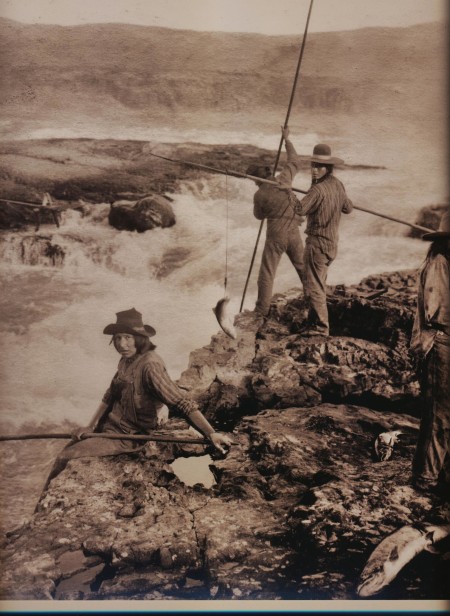

God call them home? The few survivors walked away dazed. Took to speaking other languages. Were replaced by strangers. After a few decades hardly anyone remembered that they had ever been there.” through the Gorge in 1805. We lived in three subdivisions: the Yhehuhs, who were above The Cascades of the Columbia River, the Chahclellahs, who lived below The Cascades, and the Wahclellahs, who lived near Beacon Rock. We had six villages on both sides of the river until the 1830′s, when what was called the ‘Cole Sic and Warm Sic’ (Malaria) epidemic came through and decimated our numbers to near extinction. Some number perspectives: in 1780, we numbered 3,200, in 1805, Lewis & Clark’s count was 2,800, 1,400 in 1812, and about roughly 80-100 after the epidemic of the 1830′s. The survivors then created the single village that became the Wat-la-la.

through the Gorge in 1805. We lived in three subdivisions: the Yhehuhs, who were above The Cascades of the Columbia River, the Chahclellahs, who lived below The Cascades, and the Wahclellahs, who lived near Beacon Rock. We had six villages on both sides of the river until the 1830′s, when what was called the ‘Cole Sic and Warm Sic’ (Malaria) epidemic came through and decimated our numbers to near extinction. Some number perspectives: in 1780, we numbered 3,200, in 1805, Lewis & Clark’s count was 2,800, 1,400 in 1812, and about roughly 80-100 after the epidemic of the 1830′s. The survivors then created the single village that became the Wat-la-la.

was part of a substantial population that refused to settle or stay on the reservations. Many of them came to identify themselves as Columbia River Indians, or River People, based on their shared heritage of connection to the river, resistance to the reservation system, adherence to cultural traditions, and relative detachment from the institutions of federal control and tribal governance. ”

was part of a substantial population that refused to settle or stay on the reservations. Many of them came to identify themselves as Columbia River Indians, or River People, based on their shared heritage of connection to the river, resistance to the reservation system, adherence to cultural traditions, and relative detachment from the institutions of federal control and tribal governance. ”