Recalling Celilo: An Essay by Elizabeth Woody

from the book “Salmon Nation: People, Fish, and Our Common Home.”

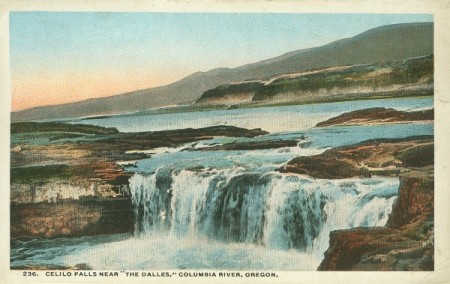

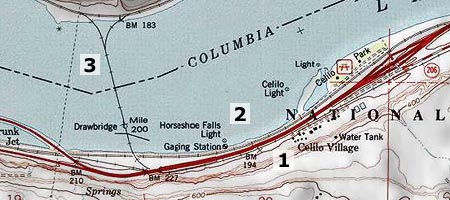

Along the mid-Columbia River ninety miles east of Portland, Oregon, stand Celilo Indian Village and Celilo Park. Beside the eastbound lanes of Interstate  84 are a peaked-roof longhouse and a large metal building. The houses in the village are older, and easy to overlook. You can sometimes see nets and boats beside the homes, though some houses are empty. By comparison, the park is frequently filled with lively and colorful wind surfers. Submerged beneath the shimmering surface of the river lies Celilo Falls, or Wyam.

84 are a peaked-roof longhouse and a large metal building. The houses in the village are older, and easy to overlook. You can sometimes see nets and boats beside the homes, though some houses are empty. By comparison, the park is frequently filled with lively and colorful wind surfers. Submerged beneath the shimmering surface of the river lies Celilo Falls, or Wyam.

Wyam means “Echo of Falling Water” or “Sound of Water upon the Rocks.” Located on the fourth-largest North American waterway, it was one of the most significant fisheries of the Columbia River system. In recent decades the greatest irreversible change occurred in the middle Columbia as the Celilo site was inundated by The Dalles Dam on March 10, 1957. The tribal people who gathered there did not believe it possible.

Historically, the Wyampum lived at Wyam for over twelve thousand years. Estimates vary, but Wyam is among the longest continuously inhabited communities in North America. The elders tell us we have been here from time immemorial.

Today we know Celilo Falls as more than a lost landmark. It was a place as revered as one’s own mother. The story of Wyam’s life is the story of the salmon, and of my own ancestry. I live with the forty-two year absence and silence of Celilo Falls, much as an orphan lives hearing of the kindness and greatness of his or her mother.

The original locations of my ancestral villages on the N’ch-iwana (Columbia River) are Celilo Village and the Wishram village that nestled below the petroglyph, She-Who-Watches or Tsagaglallal. My grandmother, Elizabeth Thompson Pitt (Mohalla), was a Wyampum descendent and a Tygh woman. My grandfather, Lewis Pitt (Wa Soox Site), was a Wasco, Wishram, and Watlala man. But my own connections to Celilo Falls are tenuous at best. I was born two years after Celilo drowned in the backwaters of The Dalles Dam.

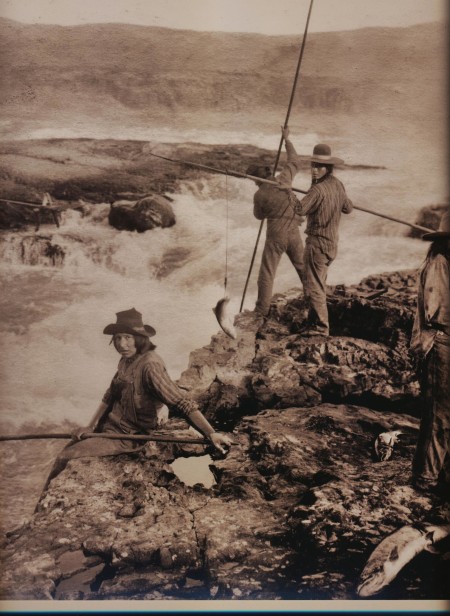

My grandfather fished at Celilo with his brother, George Pitt II, at a site that a relative or friend permitted, as is their privilege. They fished on scaffolds above the white water with dip nets. Since fishing locations are inherited, they probably did not have a spot of their own. They were Wascopum, not Wyampum.

When the fish ran, people were wealthy. People from all over the country would come to Celilo to watch the “Indians” catch fish. They would purchase fish freshly caught. It was one of the most famous tourist sites in North America. And many long-time Oregonians and Washingtonians today differentiate themselves from newcomers by their fond memories of Celilo Falls.

What happened at Wyam was more significant than entertainment. During the day, women cleaned large amounts of finely cut fish and hung the parts to dry in the heat of the arid landscape. So abundant were the fish passing Wyam on their upriver journey that the fish caught there could feed a whole family through the winter. Many families had enough salmon to trade with other tribes or individuals for specialty items.

No one would starve if they could work. Even those incapable of physical work could share other talents. It was a dignified existence. Peaceful, perhaps due in part to the sound of the water that echoed in people’s minds and the negative ions produced by the falls. Research has shown this to generate a feeling of well-being in human beings. It is with a certain sense of irony that I note companies now sell machines to generate such ions in the homes of those who can “afford” this feeling of well-being.

An elder woman explained that if my generation knew the language, we would have no questions. We would hear these words directly from the teachings and songs. From time immemorial, the Creator’s instruction was direct and clear. Feasts and worship held to honor the first roots and berries are major events. The head and tail of the first salmon caught at Celilo is returned to N’ch-iwana. The whole community honored that catch: One of our relatives has returned, and we consider the lives we take to care for our communities.

The songs in the “ceremonial response to the Creator” are repeated seven times by seven drummers, a bell ringer, and people gathered in the Longhouse. Washat song is an ancient method of worship. By wearing the finest Indian dress, the dancers show respect to the Creator.

Men on the south side, women on the north, the dancers begin to move. In a pattern of a complete circle they dance sideways, counterclockwise. This ceremony symbolizes the partnership of men and women, the essential equality and balance within the four directions and the cosmos. We each have our place and our role. As a result, the Longhouse is a special place to learn.

Meanwhile, in the kitchen, women prepare the meal. Salmon, venison, edible roots, and the various berries — huckleberries and chokecherries — are the four sacred foods. More common foods are added to these significant four on portable tables. Those who gather the roots and berries are distinguished. Their selection to gather the foods is recognition of good hearts and minds. Tribal men who have hunted and fished are likewise acknowledged. One does not gather food without proper training, so as not to disrupt natural systems.

Meanwhile, in the kitchen, women prepare the meal. Salmon, venison, edible roots, and the various berries — huckleberries and chokecherries — are the four sacred foods. More common foods are added to these significant four on portable tables. Those who gather the roots and berries are distinguished. Their selection to gather the foods is recognition of good hearts and minds. Tribal men who have hunted and fished are likewise acknowledged. One does not gather food without proper training, so as not to disrupt natural systems.

What has happened to Celilo Falls illustrates a story of inadequacy and ignorance of this land. The story begins, of course, long before the submergence of the falls with the seed of ambitions to make an Eden where Eden was not needed. One needs to learn from the land how to live upon it.

The mainstem N’ch-iwana is today broken up by nineteen hydroelectric dams, many planned and built without a thought for the fish. Nuclear, agricultural, and industrial pollution, the evaporation of water from the reservoirs impounded behind dams, the clearcut mountainsides – all are detrimental to salmon. Since 1855, the N’ch-iwana’s fourteen million wild salmon have dwindled to fewer than one hundred thousand.

Traditional awareness counsels in a simple, direct way to take only what we need, and let the rest grow. How can one learn? My uncle reminded me that we learned about simplicity first. He said, “The stories your grandmother told. Remember when she said her great grandmother, Kah-Nee-Ta, would tell her to go to the river and catch some fish for the day? Your grandmother would catch several fish, because she loved to look at them. She would let all but two go. Her grandmother taught her that.”

A larger sorrow shadows my maternal grandmother’s story of the childhood loss of the material and intangible. What if the wild salmon no longer return? I cannot say whether we have the strength necessary to bear this impending loss.

The salmon, the tree, and even Celilo Falls (Wyam) echo within if we become still and listen. Once you have heard, take only what you need and let the rest go.

•

Elizabeth Woody (Navaho/Warm Springs/Wasco/Yakama) received the American Book Award for her collection of poetry “Hand into Stone.” She is the Director of the Indigenous Leadership program for Ecotrust. This essay is adapted from Salmon Nation: People, Fish, and Our Common Home.